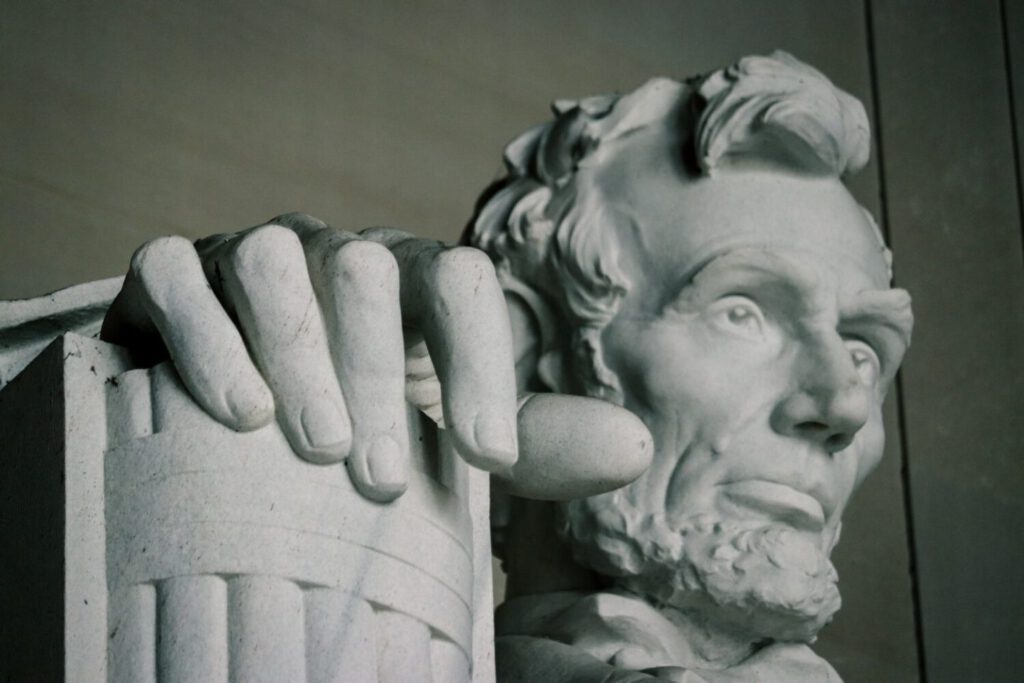

Abraham Lincoln: We Must Teach Respect for Law in Civics Education

Our nation seems to be pulling apart. Americans are increasingly divided along ideological lines over the goodness and relevance of the founding principles of our country. The violence arising out of…

Our nation seems to be pulling apart. Americans are increasingly divided along ideological lines over the goodness and relevance of the founding principles of our country. The violence arising out of last summer’s protests and the violence at the U.S. Capitol on January 6 suggest that more and more Americans have lost confidence in our governing institutions and the possibility that justice will be served through the rule of law. Even if these violent episodes were only one-time events, each act of mob violence, especially if left unpunished, will suggest to the “other side” that justice is best pursued through aggressive assertions of force rather than reliance on slow-moving legal institutions.

Abraham Lincoln addressed an even more fraught and apparently lawless situation in 1838 when he delivered his famous Lyceum Address. He was only in his late 20s, but he recognized that mob violence threatened more than an intensification of hatreds and violence among partisans. In such a situation, Lincoln suggested that citizens who would have once revered our national institutions would also lose respect for the law through weak and selective enforcement. Even those upright citizens would be open to an American Napoleon or Caesar if our own popularly elected institutions could not command enough respect to enable them to survive.

Lincoln points out that strong and patriotic American feelings toward the country were able to override some of these challenges for a time. For a while, Americans could be united to each other and to the laws of their country by feelings of hatred toward the British. Then, they were assisted by strong living memories of their ancestors who had risked or even sacrificed their lives for the cause of Independence. We might have been in an analogous situation of attachment to the laws through strong emotional attachments in the aftermath of America’s struggle against Nazi Germany or in the aftermath of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. However, Lincoln teaches us that we cannot ultimately rely on fading feelings to protect our institutions and the laws.

His solution to the problem of waning patriotic feeling and lack of public confidence in institutions was a vigorous commitment to civic education at every level of society:

Let reverence for the laws, be breathed by every American mother, to the lisping babe, that prattles on her lap—let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; –let it be written in Primmers, spelling books, and in Almanacs; –let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice.

In Lincoln’s first unsuccessful run for the Illinois state house in 1832, he proposed universal education so that everyone would be able to “read the histories of his own and other countries, by which he may duly appreciate the value of our free institutions.” How would civics education solve the problem of social disintegration and weakened attachment to the rule of law? Renewed attention to civics education could provide Americans with an account of the reasonableness and decency of American institutions and could train young minds to think of the law as not merely the creation of arbitrary human decisions but in some way as a reflection of the laws of nature and nature’s God, to which all people—even champions of self-government and popular sovereignty—are ultimately subject. The histories of our own country can help connect Americans of even very young ages to the broader American story. They can inspire new generations with examples of virtuous statesmanship, which in turn would suggest that there is something important about the principles and institutions that those great Americans were advancing.

In our own time, a renewal of civics education can satisfy many of the same aims. In a society with fraying attachments to our laws and institutions, we must follow Lincoln and once again present the timeless and reasonable principles of the Declaration of Independence to the next generation. The principles of the Declaration and our institutions tie great Americans of every generation to each other and can teach us to accept—and even revere—the rule of law.