Are charter schools re-establishing racial and ethnic segregation? Not so fast!

A research paper in Demography, a journal publication of Duke University Press, raises the specter of renewed racial segregation in K-12 education due to the impact of charter schools.

While…

A research paper in Demography, a journal publication of Duke University Press, raises the specter of renewed racial segregation in K-12 education due to the impact of charter schools.

While education and housing segregation typically mirrored each other, due to the linking of a student’s residence to their neighborhood school, the study’s authors claim the advent of school choice – as expressed in the proliferation of charter schools in the last 20 years – has facilitated a new segregation by choice not dissimilar to the old segregation by law.

The racist policy of “redlining” dominated the development of housing, and by extension, school building during the early to mid-20th century in large urban and suburban areas in America. School enrollments and residence locations were traditionally bundled together.

With public school enrollments based on residence, racially segregated neighborhoods inherently resulted in racially segregated public schools, in violation of the U.S. Constitution. This circumstance led to Brown v. Board of Education, a landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in public education.

However, the elimination of de jure racial policies alone had little effect on existing school segregation since school enrollments were still tied to neighborhoods. What had been de jure became de facto in the wake of the Brown decision.

Desegregation plans were implemented across the country, using busing, magnet schools and early forms of open enrollment policies to artificially strike a racial balance in all schools.

However, not all parents of minority children were thrilled with the new structures, which often saw children riding buses for long periods each day to attend schools where they had few, if any, friends.

Moreover, the increased economic power of black families brought on by the Reagan economy of the early 1980s, and decreasing racism within society at large, occasioned a significant departure of black families from inner-city neighborhoods, as they decamped to majority white suburbs where both schools and housing were better.

An unintended but foreseeable consequence of forced desegregation policies then gave witness to “white flight,” as white families moved out of large school districts under court-directed desegregation plans to smaller, surrounding districts unaffected by federal orders.

These trends are claimed by some to be evidence of continued segregationist thinking, a subcurrent of racism built-in to American society. A Brookings Institution study declares this to be true, but provides dubious evidence for that conclusion.

The data showing white, black, or Hispanic enclaves in a given city or region is presented as sufficient evidence on its own to prove segregation is with us today. But what is not addressed is the very real sociological drive to recognize (and find comfort in) faces like our own.

Own-race bias (ORB) refers to the phenomenon by which own-race faces are better recognized than faces of another race. Own-race bias has been extensively researched and, notably, is found consistently across different cultures and races, including individuals with Caucasian, African and Asian ancestry, and in both adults and children as young as 3-month-old infants.

Rather than addressing the various social elements of racial congregation, politically motivated sociologists lay the blame on “exclusionary zoning practices” and “land use” requirements. But the presence of racial enclaves in neighborhoods does not declaratively indicate racism as a driver when similarly impactful pressures such as ORB, cultural affinity and shared social norms are also in play.

The study on charter schools published in Demography decries the decoupling of neighborhoods from their physically proximate schools and cites the growth of charter schools as the new vehicle of racial and economic segregation.

These studies are markedly white-centric, as they factor only the impact of decisions made by white populations in extrapolating racist outcomes. None of the research cited above has considered that minority families may have chosen to reside in neighborhoods that present greater cultural, social, and yes, even racial, homogeneity for themselves and their children.

Economic pluralism has enabled racial and ethnic minorities to locate wherever their financial capacity can sustain them. Charter schools are downstream of that relocation, serving preexisting needs, not driving relocation to avoid diversity.

The idea of “racial sorting” in suburbs is self-explanatory when viewed through a broad lens. Even the Duke study admits:

“In the 1990s, charter schools opened in racially segregated Black and Hispanic neighborhoods of large cities. Many families were attracted to the alternative charters provided to historically under resourced TPSs (traditional public school) that had large class sizes and offered parents little power (May 2006; Reid and Johnson 2001; Renzulli 2006). Further, in many predominantly Black cities, racially homogenous schools advance an Afrocentric mission that may be attractive to Black parents and students.”

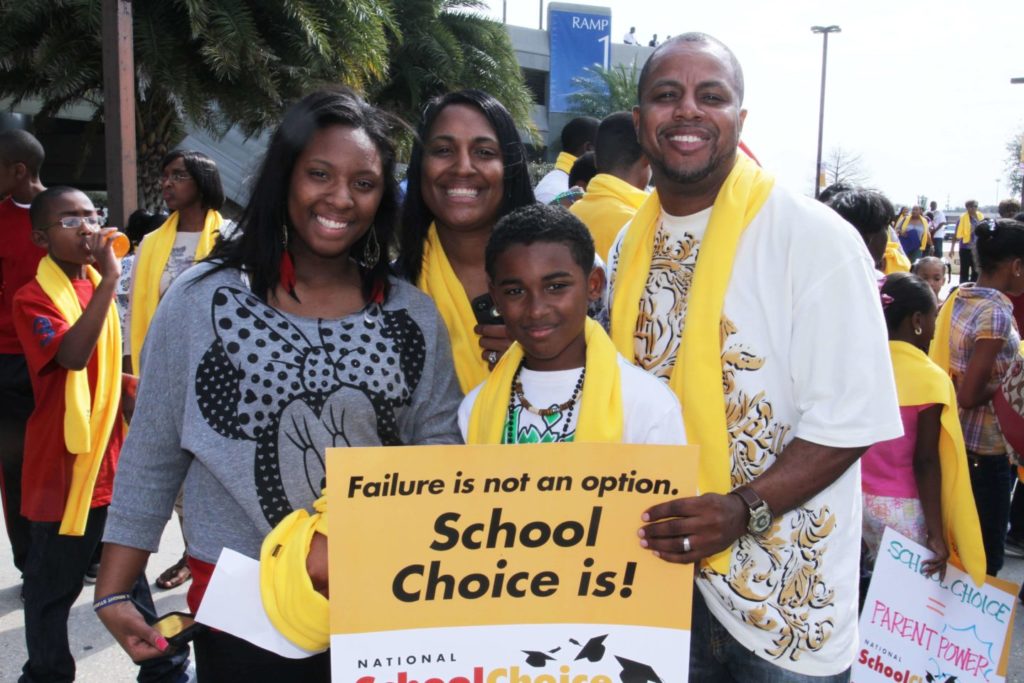

The advent of choice in elementary and secondary education has permitted sorting of an organic nature, not a racist one. Charter schools have found success not by excluding undesirable students, but by offering students an alternative to the rigidity of formulaic racial and ethnic quotas.

Choice is always preferable – even if the results of free choice don’t always look the way you thought they should.