Court leaves Texas’ six-week abortion ban in effect and narrows abortion providers’ challenge

Nearly six…

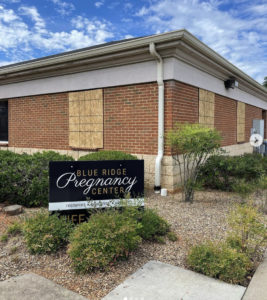

On Friday, the court released opinions in the two Texas abortion cases heard in November. (Beechwood Photography via Flickr)

Nearly six weeks after the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in two cases challenging a Texas law that bans almost all abortions in the state, the justices on Friday limited – but did not fully eliminate – the ability of abortion providers to continue their challenge in the lower courts. The court ruled that the providers’ lawsuit can go forward against a group of state medical licensing officials, but not against the state-court judges and clerks whom the providers had also tried to sue.

The Texas law, known as S.B. 8, remains in effect. The ruling in the providers’ case, Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson, allows the providers to return to the lower courts and seek an injunction against the licensing officials, but it’s not clear how much relief that could provide from a law that intentionally relies on private citizens for enforcement. The justices also declined to weigh in on a separate challenge to the Texas law brought by the Biden administration, and they denied the administration’s request to put the law on hold.

S.B. 8, which took effect on Sept. 1, bars doctors from performing abortions starting around the sixth week of pregnancy, except in cases of medical emergencies. That is a clear conflict with the Supreme Court’s landmark decisions in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which establish a right to an abortion up to the point at which the fetus becomes viable, which normally occurs around the 24th week of pregnancy. The future of Roe and Casey is squarely at issue in a separate case involving Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban that the justices heard last week. The question before the court in the Texas providers’ case centered on S.B. 8’s unusual enforcement mechanism, which delegates the sole power to enforce the law to private individuals, rather than state officials. The law allows anyone to bring a lawsuit in state court against anyone who performs an abortion or helps to make one possible, with at least $10,000 in damages available for a successful lawsuit.

A group of clinics and other abortion providers filed a challenge to the law in federal court in July, seeking to block S.B. 8 before it could go into effect. That challenge first arrived at the Supreme Court in late August, with the providers asking the justices to put the law on hold while the challenge proceeded in the lower courts, but the justices declined to do so. The providers returned to the court in the fall, asking the justices to weigh in on the law’s private-enforcement mechanism. The justices agreed in late October to take up their case along with the Biden administration’s challenge to the law, United States v. Texas, and fast-tracked the two cases for oral argument on Nov. 1.

In an 18-page opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch began by emphasizing that the court was not ruling on whether S.B. 8 is constitutional or whether it is a good idea “as a matter of public policy.” Instead, the question was whether the providers can pursue their challenge to the law against specific defendants before the law is enforced. The providers, Gorsuch explained, cannot sue to block state-court clerks from docketing lawsuits under S.B. 8, nor can they sue to block state-court judges from hearing such cases. Among other things, Gorsuch reasoned, state-court judges and clerks are not adversaries to the providers; they are neutral actors. So a pre-enforcement challenge against judges or clerks does not qualify as the kind of “controversy” required under the Constitution to bring a case in federal court, Gorsuch wrote.

The providers also cannot sue the state attorney general, Ken Paxton, to prevent him from enforcing S.B. 8, Gorsuch continued. Gorsuch noted that the providers had not pointed to any source of authority for the attorney general under S.B. 8, so that there wouldn’t be anything for a federal court to block him from doing. And even if he did have such power under S.B. 8, Gorsuch added, that would not give federal courts the power to block lawsuits under S.B. 8 by private individuals or to block the law itself.

Four other justices – Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett – agreed with Gorsuch on these points, creating a 5-4 majority to prevent the providers from proceeding with their lawsuit against the judges, the clerks, or Paxton.

In a separate part of the opinion, eight justices – everyone but Thomas – held that the providers’ lawsuit could go forward against state officials responsible for medical licensing and the head of the Texas health department. Gorsuch noted that the providers had “identified provisions of state law that appear to impose a duty on the licensing-official defendants to bring disciplinary actions against them if they violate S.B. 8.”

Finally, all nine justices ruled that the providers’ claims against Mark Lee Dickson, an anti-abortion activist whom the providers believed would be likely to sue them under S.B. 8, could not go forward because Dickson had averred that he has no intention of doing so.

Chief Justice John Roberts filed an opinion that was joined by the court’s three liberal justices – Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. Roberts agreed that the providers’ suit should be allowed to go forward against the licensing officials, but he would have allowed the rest of their suit to proceed as well. He emphasized that S.B. 8 “has had the effect of denying the exercise of what we have held is a right protected under the Federal Constitution.” And because of the “ongoing chilling effect of the state law,” Roberts opined, the district court “should resolve this litigation and enter appropriate relief without delay.”

Roberts then addressed the impact of S.B. 8 more broadly, observing that its “clear purpose and actual effect” “has been to nullify this Court’s rulings.” If state legislatures can pass laws to undo the rights created by the federal courts, Roberts stressed, “the constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery.” “The nature of the federal right infringed does not matter; it is the role of the Supreme Court in our constitutional system that is at stake,” Roberts concluded.

Sotomayor also filed her own opinion, joined by Breyer and Kagan, in which she emphasized that “[f]or nearly three months, the Texas legislature has substantially suspended a constitutional guarantee: a pregnant woman’s right to control her own body.” The Supreme Court, she wrote, “should have put an end to this madness months ago, before S. B. 8 first went into effect,” but it did not do so then or now. Like Roberts, Sotomayor joined the portion of the court’s decision allowing the providers’ lawsuit against the licensing officials to go forward, but she explained that she dissented from “the Court’s dangerous departure from its precedents, which establish that federal courts can and should issue relief when a State enacts a law that chills the exercise of a constitutional right and aims to evade judicial review.” By precluding lawsuits against state officials, including the state attorney general, Sotomayor suggested, “the Court effectively invites other States to refine S.B. 8’s model for nullifying federal rights.”

Thomas wrote a separate opinion as well. He said he would not have allowed the providers’ lawsuit to go forward at all.

At the same time that it released its decision in the providers’ case, the court issued a brief, unsigned order, dismissing the Biden administration’s challenge to the Texas law as “improvidently granted” – a disposition that does not resolve the case on the merits. The justices also denied the administration’s request, originally made in October, to put S.B. 8 on hold. Sotomayor was the only justice to note a dissent from the order.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.