Education bureaucracy pushing the status quo in hearings

(The Sentinel) – Legislative hearings over this and last week are focusing on how to improve outcomes in Kansas education, perhaps unsurprisingly, the education bureaucracy is arguing…

(The Sentinel) – Legislative hearings over this and last week are focusing on how to improve outcomes in Kansas education, perhaps unsurprisingly, the education bureaucracy is arguing for the “status quo.”

For years school funding in Kansas was the subject of a series of lawsuits, with schools arguing that the state had not met its constitutional duty to provide “adequate and equitable” funding for education. Indeed, districts advanced the argument that achievement issues in Kansas were largely due to school funding and that more money was needed.

However, after the Gannon lawsuit was resolved and the Kansas Supreme Court ruled that funding was both equitable in 2018 and adequate in 2022 the state has not seen much in the way of improvements in education outcomes.

Gannon was filed on election day in November of 2010, the day former Republican Governor Sam Brownback was elected because of cuts made under the watch of former Democrat Governor Mark Parkinson.

Indeed, it is clear that achievement is actually worse post Gannon than before.

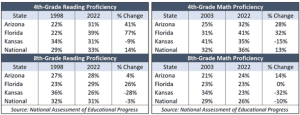

In fact, Kansas scores are below the national average in nearly every category on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) exams; NAEP scores are the best way of comparing achievement across the states.

For example, in 2022 40% of Kansas 4th graders and 33% of Kansas 8th graders scored as reading below a basic level — which the National Center for Education Statistics defines as “partial mastery of fundamental skills.” Not reading at the basic level then indicates that the student does not have a “partial mastery of fundamental skills.”

Two decades ago, on the 2003 NAEP exam, 34% of 4th graders, and 23% of 8th graders were below basic.

Only 31% of 4th graders and 26% of 8th graders scored as “proficient” in 2022. Likewise, the “proficient” numbers have gotten worse as well. In 2003 35% of 4th and 33% of 8th graders were considered “proficient” in reading.

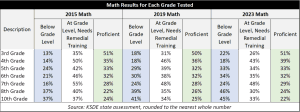

Math scores were troubling as well, even on the state’s own exam, with state assessment scores showing a distinct drop in proficiency from 3rd grade to 10th grade.

For example, testing from the end of the previous school year shows that 48% of third graders were below grade level or were at grade level, but needed remedial training, with 51% scoring “proficient.”

However, those numbers begin to drop significantly with each grade level so that by the 10th grade 45% of students are below grade level in math, 33% need remedial training and only 22% are considered proficient.

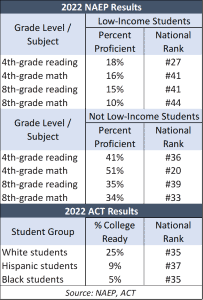

The 2022 NEAP scores highlight serious concerns about the achievement gaps between low-income and not low-income students as well. It isn’t just one metric either as the 2022 Kansas ACT, a standard college entrance exam, scores show only 25% of White students, 9% of Hispanic students and 5% of Black students are “college ready.”

Rather than try to provide a way forward, however, the education bureaucracy instead defended the status quo.

Indeed the Kansas State Department of Education insisted that it was impossible to say how many students are “below grade level” because the state assessment “only tests at grade level,” on a four level scale, with level one being “below academic expectations for grade level” and Levels 2, 3, and 4 being at or above grade level.

“Because we do not have off-grade level items (on the state assessment) we only test based on what is grade level,” Dr. Ben Proctor, KSDE deputy commissioner said. “We don’t really have a descriptor of whether someone is below or above grade level, just how they’re performing at that grade level based on those descriptors.”

However, as Kansas Policy Institute CEO, Dave Trabert pointed out in a recent editorial for the Sentinel, which is owned by KPI, this is disingenuous at best.

“They acknowledge that about a third of students have limited ability to perform at grade level, which obviously means those kids are not performing at grade level,” he wrote. “But KSDE doesn’t like the ‘below grade level’ label because it sounds bad (which it is), so it scrubbed ‘grade level’ from the description for the sake of appearance. Originally, Level 1 was clearly ‘below grade level’ because Levels 2-4 were identified as ‘at or above grade level.’

Even the Kansas Supreme Court wrote, ‘Level one is students who are not performing at grade level in the given subject.’”

Moreover, the Kansas Association of School Boards insisted that Kansas is one of just six states that didn’t experience a decline in ACT scores in 2022. Of course those scores were identical to the 2021 scores and those were the worst in 30 years.

The mantra, however, has not changed “we need more money.”

Instead of addressing the issues those scores revealed, Scott Rothschild, the communications editor for KASB, instead dismissed the tests, saying that some kids just don’t test well. He also blamed them on the pandemic and insisted the issues were related to funding.

Rothschild additionally noted that Kansas scores are around the national average, which is true, but the national scores aren’t any better, and directly tied test scores to funding.

“Kansas funding was below inflation and takes a real dip from 2009 to 2015,” he said. “Total Kansas funding dropped from 98% of the U.S. average in 2009 to 88% in 2019. Over that period Kansas NEAP scores fell from above the U.S. average to about the same as the U.S. average. Kansas began increasing school funding more than inflation in 2018 under the 6-year funding plan in response to Gannon but as you can see we are still below the national average by about 10% and we are just about the regional average.”

“I would be shocked to hear if anyone uh anyone in this room or if anyone you know got a job based on what they scored on a state assessment,” he said. “What public schools need is reliable funding, including for special education, community and parental involvement and supportive partners in the legislature.”

Senator Molly Baumgardner took special exception to the idea that funding was “unreliable.”

“Is it KASB’s position that funding for school districts isn’t reliable since the Supreme Court of the state ruled that it was appropriate and they signed off on it?” she asked.

Rothschild admitted, under pressure, that funding had been reliable for the last several years.

Kansas State Rep. Kristey Williams, who chairs the interim committee on education, in a statement to the Sentinel, took exception to that characterization.

“If more money is the answer, what improved outcomes will Kansans see as a result?” she said. “It’s time we look at root causes for academic decline and make an honest effort to address those challenges. We need to be serious about improving outcomes and helping our most vulnerable kids succeed. If adding more money is the only solution offered, then we clearly have a red flag.”