‘Grade grubbing.’ Some high school and college students want good grades without the work, says survey

A survey of nearly 300 high school teachers and college professors found that students frequently ask for better grades than they’ve earned, also known as grade grubbing.

Some of the most…

A survey of nearly 300 high school teachers and college professors found that students frequently ask for better grades than they’ve earned, also known as grade grubbing.

Some of the most common reasons given for grade grubbing were illness (35%), the class’s difficulty (41%) and personal trouble (59%). Only one-third of the complaints alleged the grading itself was unfair.

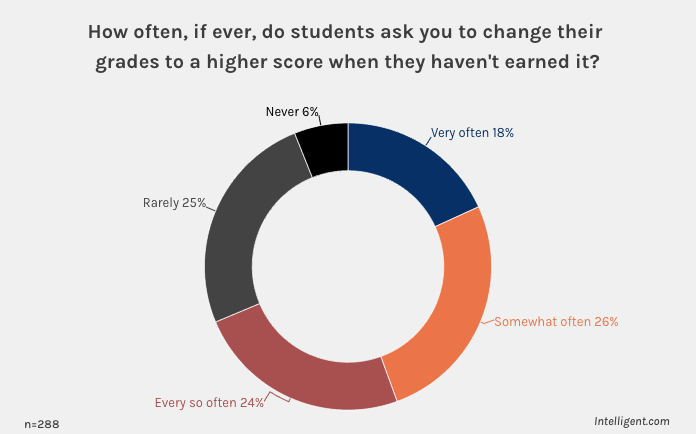

Sixty-eight percent of educators reported hearing these pleas very often, somewhat often, or every so often. Only 6% never heard them.

“Anecdotally, there appears to be an increase in the frequency of students trying to negotiate higher grades,” said Diane Gayeski, a professor of strategic communication who also has a Ph.D. in educational administration.

“While there’s not a lot of research on this yet, in a study of undergraduate students preparing for careers in medicine, ‘over a quarter of the respondents self-reported engaging in grade-focused interactions… Of these individuals, 71% were successful in their negotiation for a higher grade,” she said.

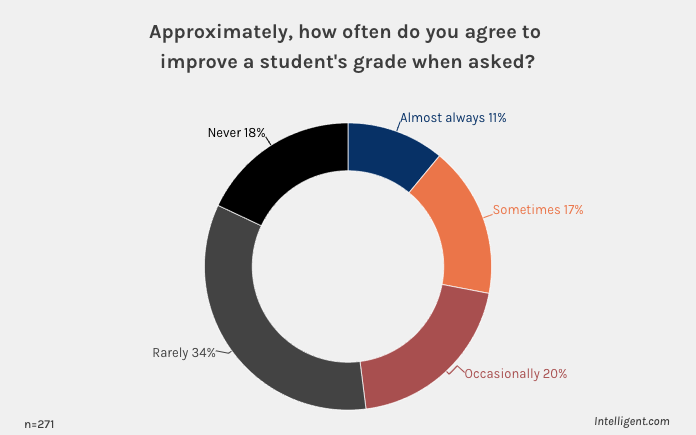

Most teachers have agreed to change a grade at one time or another, but they reportedly do so at a much lower rate than students ask, according to the survey.

Only 11% are “almost always” willing to change a grade, while 52% are “never” or “rarely” willing to do so.

Additionally, 45% of educators believe that Gen Z – the generation born between 1997 and 2012 – “grade grub” more frequently than others.

The survey also found a significant number of teachers are punished for giving poor grades.

Many teachers reported having been harassed by students (38%) or parents (33%), reprimanded by supervisors (30%), or even fired (7%) over giving poor grades.

Only one-third had never suffered any ill-effects of giving undesirable grades.

There have even been stories of students murdering their teachers over grade disputes.

Earlier this year, two Iowa teenagers plead guilty to murdering their female Spanish teacher, 66, for giving them a bad grade.

In 2016, a UCLA student who was “despondent” about his grades killed his professor and himself.

While such incidents are rare, grading standards are being hotly debated nationwide.

Many school districts have promoted grading policies that make failure virtually impossible. For example, Kansas City Public Schools forces teachers to give students 40% credit in the name of “equity” – even if nothing is turned in.

A district in Nevada did something similar, except its minimum was 50%.

Such “grade inflation” is evident in states like Kansas where graduation rates do not reflect plummeting test scores in basic subjects like reading and math.

Tom Horne, the Arizona state superintendent, recently criticized the practice.

“We have a war between excellence and mediocrity. So-called ‘equitable,’ ‘compassionate,’ or ‘standards-based’ grading promotes mediocrity,” Horne said in May. “If we are to increase learning and show it in increased test scores, students must do homework and be graded objectively. The parents of the state are demanding this result.”

Research shows that having high grading standards helps students of all ethnicities and income levels be more successful.

“Lax grading is a pernicious practice that provides students and parents with a false sense of security and accomplishment,” said researcher and economist Seth Gershenson. “Low grading standards pose a grave threat to the performance and evaluation of U.S. public schools that ultimately jeopardizes the competency of high school and college graduates who are entering the workforce.”

Indeed, colleges are finding that high school graduates are less prepared for rigorous academics than before. Even prior to the pandemic, college readiness was at its lowest in 15 years, according to the ACT website.