Kansas bill would create a tax credit for private and home school families

(The Sentinel) – A Kansas bill that would provide a tax credit to families whose children are in either private school or are homeschooled passed an important procedural hurdle last week when the…

(The Sentinel) – A Kansas bill that would provide a tax credit to families whose children are in either private school or are homeschooled passed an important procedural hurdle last week when the Kansas Senate Committee on Assessment and Taxation recommended SB 509 be passed by the full chamber.

Senate Bill 509 would create an income tax credit of 75% of Base State Aid for Excellence (BASE) for Kansas residents with children enrolled in an accredited nonpublic school, i.e. private school, and 50% for children enrolled in “a nonaccredited private elementary or secondary school registered with the (Kansas State) Department of Education.”

If passed, for tax year 2024 — the first year for which the bill would be effective — the tax credit would be capped at $75 million but would be increased by an additional 25% for any year in which the number of credits claimed was 90% or more of the cap.

BASE is currently $5,088 per student. Eligible families could therefore claim a credit of approximately $3,816 if their child is in private school or about $2,544 for children attending non-accredited schools, significantly offsetting the cost of private school tuition or purchasing curricula and supplies for homeschooling — often a barrier to leaving public education.

As a refundable tax credit, the “Education Opportunity Tax Credit,” as it is called, would not be automatic, but parents would have to specifically claim the credit and provide a valid social security number for each child claimed, and the Kansas Department of Revenue would have to verify with KSDE the enrollment status of the child.

James Franko, president of the Kansas Policy Institute — which owns the Sentinel — testified in support of the bill.

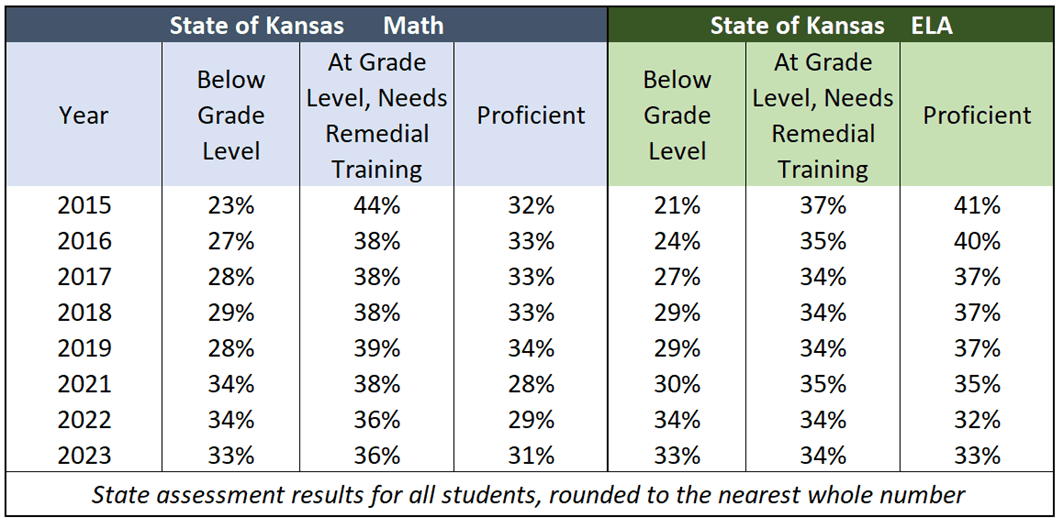

Franko noted that, while support for school choice is strong in Kansas, progress toward choice in the Sunflower state has been slow, while student achievement has been declining precipitously. One-third of students are below grade level in reading and math, and only about a third are proficient.

“Certainly, many kids receive a quality education in Kansas, but the facts also make clear that many do not,” Franko said. “This fact is true across districts and the state. This is true despite the best efforts of countless teachers, counselors, paraprofessionals, and others working in our public schools.

“I would also like to point out the stagnating overall achievement in Kansas schools and the staggering achievement gaps between low-income and non-low-income children,” he continued. There are many reasons for these long-term trends, and they must be addressed.”

Franko noted that while there is no “silver bullet” for fixing the achievement issues in the state, giving parents more opportunities to find the proper educational “fit” for their children will help — particularly for at-risk populations such as children in foster care or low-income families.

Franko also reiterated that school choice exists in every state — if they have the money.

“We have school choice in Kansas — for the families that can afford it,” he said. “But not everyone can afford it.”

Tax credit opponents defend the system and ignore student needs

Unsurprisingly the education establishment, from KSDE to the Kansas State Board of Education oppose to the bill — even though it does not directly affect funding for public schools.

During the hearing, Senator Tom Holland (D-Baldwin City), asked Franko if he thought it was a “core mission for the state of Kansas to provide a quality public education for every child in this state?”

Franko said the goal should be a quality education, period.

“I think it is incumbent upon the state to provide a good education for every student in the state, whether that is in a private institution or any other kind of institution,” he said.

Holland pressed, asking — given that the state is already providing a public education for every child — “why should the state take on the burden of, in essence, funding a private education?”

Franko noted that the data clearly shows “that one system does not work equally well for every child.”

Moreover, Holland failed to note that parents of private school or homeschool children are still funding public education through their property taxes — but not actually using the service they are paying for.

Holland then tried to suggest that the bill would be akin to a group of residents deciding they want a private police force and then getting the legislature to pass tax credits to pay for it.

Senator Renee Erickson (R-Newton), noted that if a police force was only effective 30% of the time, it might be appropriate for a community to look at a private option that met their needs more fully — particularly if it could be done without taking funding away from the existing service.

In written testimony, Leah Fliter, Assistant Executive Director for Advocacy for the Kansas Association of School Boards, predictably tried to suggest that SB509’s tax credit would divert money from public schools.

“SB 509 would appropriate an unknown amount of income tax revenue from the State General Fund and funnel it to income-tax vouchers for undefined and unregulated spending and away from the public schools that serve nearly 500,000 Kansas children,” she wrote. “SB 509 does not require the non-accredited schools that would utilize the income-tax voucher to demonstrate their students are making any kind of academic progress. SB 509 doesn’t require background checks for the staff of the non-accredited schools that would profit from the voucher.”

Fliter consistently tries to suggest accountability restrictions on private schools that are not imposed on public schools. In this case, public schools do not have to demonstrate that students are making progress. Indeed, outcomes have significantly declined without consequence to public schools.

“Non-accredited” is generally a euphemism for “homeschooled,” and research shows that homeschooled students tend to test 15 to 25 percentile points higher than public school students — putting them in the upper 75% percent of students. Moreover, the “staff” at most “nonaccredited schools” are — parents.

Deena Horst and Ann Mah, both of KSDE, also wrote in opposition.

They repeated the “accountability” argument and also posited a hypothetical argument in which a court finds the tax credits constitute “state funding” of nonpublic schools.

“Given the number of court cases that have dictated how public schools must operate, what discipline may be imposed, etc., because they are funded by tax dollars, it is surprising that non-public schools would even be interested in receiving tax dollars,” they wrote. “If the nonpublic school accepts students whose parents receive funds through tax dollars, will they now be required to serve that student regardless of possible learning or behavior issues?”

As is often the case, Horst and Mah cited no legal basis for their opinions and completed ignored that many students are below grade level in public schools.

And while communicating a possible lawsuit by districts, they ignored the fact that, as a tax credit to parents, the nonpublic school is not receiving tax dollars directly.

Ultimately, Franko said, the goal should not be to have good public schools simply for the sake of having good public schools.

“The goal is to give every Kansas child the opportunity to succeed,” he said. “That will mean attending a high performing public school for most children, but it should also include a different avenue for children where the local public school is not the right fit.”