KC Star in government public relations mode on Kansas education

(The Sentinel) – If there was an award for journalistic malpractice, the Kansas City Star would be a leading contender.

The most recent example of the Star’s ‘government good / Republicans…

(The Sentinel) – If there was an award for journalistic malpractice, the Kansas City Star would be a leading contender.

The most recent example of the Star’s ‘government good / Republicans bad’ political philosophy is a story about special education funding. It leads with a touching story on a young special education student to justify a $360 million annual funding increase for special education, which arguably is not necessary. The experience of that youngster and their family is personally poignant, but the larger argument of the piece ignores the reality of special education funding and districts’ spending decisions.

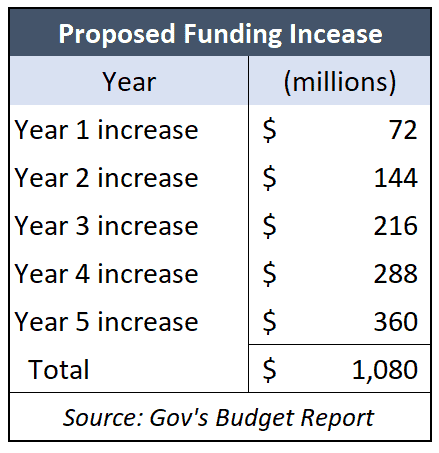

The Star and education officials say Governor Kelly is proposing a $72 million increase, but that is an annual increase over five years, which means she is proposing a total increase of $1.08 billion. The fully-implemented cost of $360 million is more than twice what school officials say they are ‘owed,’ and responsible reporters would ask for justification for such a generous increase. But not the KC Star. It operates more like a public relations machine for the government.

The Star and education officials say Governor Kelly is proposing a $72 million increase, but that is an annual increase over five years, which means she is proposing a total increase of $1.08 billion. The fully-implemented cost of $360 million is more than twice what school officials say they are ‘owed,’ and responsible reporters would ask for justification for such a generous increase. But not the KC Star. It operates more like a public relations machine for the government.

Making false claims is another indicator of journalistic malpractice. The story says, “Kansas Rep. Kristey Williams, an Augusta Republican, previously floated reallocating some of that general education money to only special ed.” That makes it sound as though she is trying to pull a fast one, but in reality, she is trying to resolve what appears to be a mistake in the special education funding formula.

The formula that calculates the state’s share of special education costs inadvertently does not count weightings for at-risk, bilingual, career & tech ed, transportation, and high-density at-risk, even though Deputy Commissioner Craig Neuenswander says special ed students would receive the funding associated with those weightings. It also excludes Local Option Budget (LOB) money related to special education funding. The LOB money related to the regular education funding for special ed students is part of the formula, but Neuenswander doesn’t know why all of the LOB money isn’t counted.

Special education funding generates LOB money based on each district’s LOB rate, which can go as high as 33%. So, a district with a 33% LOB rate that gets $1 million in special education aid also collects $333,000 in LOB money from local taxpayers because of its special education funding.

The Legislature provided $323 million more than required if the LOB funding that was generated by special education aid over the last five years was included in the formula, and that does not count funding for the weightings excluded in the formula.

Districts aren’t spending all of the funding they receive

It takes hutzpah to say you are underfunded when you aren’t spending all of the money you’re getting. The KC Star knows that districts are increasing cash reserves, but not sharing that information is another example of journalistic malpractice.

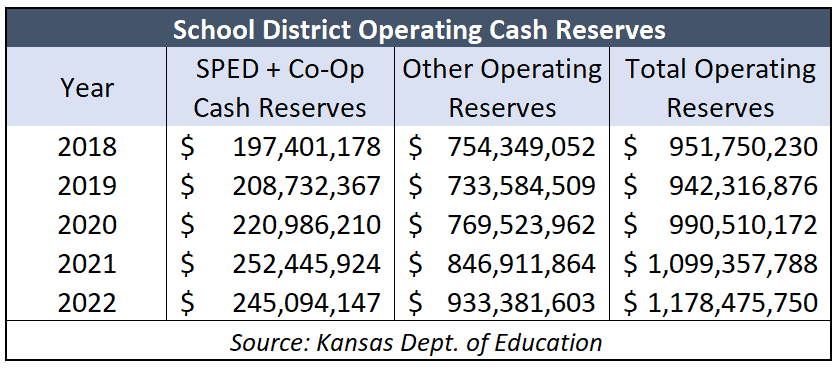

School districts had $952 million in operating cash reserves at the end of the 2018 school year, and that doesn’t count money set aside for capital outlay, debt service, or federal funds. The total jumped $227 million by the end of the 2022 school year to $1.178 billion.

School districts had $952 million in operating cash reserves at the end of the 2018 school year, and that doesn’t count money set aside for capital outlay, debt service, or federal funds. The total jumped $227 million by the end of the 2022 school year to $1.178 billion.

Cash reserves function like your checkbook; the balance increases each year if you deposit more than you spend. That means most of the increase in cash reserves results from districts not spending all of the money given to them by taxpayers.

Special education cash reserves are part of the operating total. Those balances increased by $48 million, and all other operating reserves increased by $179 million.

Shawnee Mission, one of the districts that decried the lack of funding in the KC Star article, added $8 million to its special education cash reserves over the last five years and another $16 million to its other operating cash reserves.

Using teachers, parents, and students to leverage more money

Many school officials, the Kansas Association of School Boards, and those who engage in journalistic malpractice have all of this information, yet they shamelessly use teachers, parents, and students to squeeze more money from taxpayers.

- Top-heavy, cash-rich USD 229 Blue Valley callously denied dyslexia services to students with medical diagnoses, telling parents that the district doesn’t get extra funding for dyslexia. That’s like refusing to teach math because the funding formula doesn’t provide specific allocations for math.

- Even after the Kansas Supreme Court declared funding to be constitutional (which included special education, by the way), district and building administrators make teachers pay for classroom supplies out of their own pockets and put the blame on

- Shawnee Mission officials claim not to have funding for special education and other student services in the KC Star story, but funding for extra administrators is plentiful. Enrollment is down 5% since 2005, but the district has 13% more managers.

Give kids a fighting chance with school choice

This latest example of journalistic malpractice reinforces two truths: corporate media shapes the news to fit its political agenda, and most education officials prioritize institutional demands over student needs.

Giving Kids a Fighting Chance with School Choice tells one story after another of education officials consciously deceiving parents…de-emphasizing academic preparation…and even ignoring laws designed to close achievement gaps and improve outcomes for all students. Lest anyone think private schools can’t help special education students – a common argument made by anti-choice bureaucrats – we need look no further than Oklahoma and The Lindsay Nicole Henry Scholarship program. This is a school choice program specifically for special education students.

The system (management, not teachers) shows over and over that it will not address the student achievement crisis, so the Legislature is taking a hard look at school choice legislation. For many legislators, it comes down to choosing to give those who want it another opportunity or condemn them to a lifetime of underachievement.