‘Mission creep’: Missouri K-12 spending has doubled to $15B even though enrollment is shrinking

Over the past 20 years, Missouri has lost 30,000 K-12 students but managed to nearly double its education budget – from $8 billion to $15 billion.

Data from Missouri’s Department of…

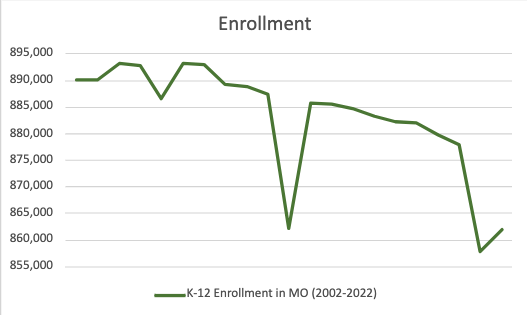

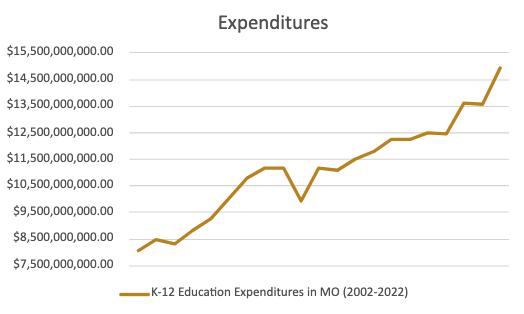

Over the past 20 years, Missouri has lost 30,000 K-12 students but managed to nearly double its education budget – from $8 billion to $15 billion.

Data from Missouri’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) reveals the state’s K-12 enrollment has dropped from over 893,000 in the early 2000’s to 862,000 in 2022.

The enrollment deficit is caused by many factors, such as families switching to homeschools, private schools, or simply keeping their young children home from early grades, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. And Missouri’s birth rates are declining even faster than the national average.

Whatever the reason, experts project the K-12 population will continue shrinking in Missouri, and across the nation.

The National Center for Education Statistics estimates Missouri will have as few as 792,000 students in 2031 – fewer students than in 1990.

“We will have excess capacity and too many teachers in most districts unless we make the region and the state more attractive to families,” wrote Susan Pendergrass, director of education policy at the Show-Me Institute. “Districts can no longer rest on their laurels and assume their classrooms will be filled.”

However, while enrollment decreased, education expenditures skyrocketed, increasing from $8 billion to $15 billion in the same 20-year span.

And inflation can’t explain all the new expenditures – especially when taking decreased enrollment into account.

Even if Missouri had the same number of students and even after accounting for inflation, current spending would still outstrip what it was two decades ago by nearly $2 billion.

So, what is that extra money paying for?

According to state Rep. Doug Richey, R-District 38, as much as 40% of DESE’s budget goes to non-education related programs – a phenomenon he describes as “mission creep.”

Richey told The Lion that DESE receives funding for a multitude of programs that have nothing to do with K-12 education, including Social Security disability determination and residential facilities for developmentally disabled adults

“Next session I will be working on the mission creep issue within DESE’s budget … to be more transparent, more accurate shall we say, with what DESE actually is receiving for K-12 education, so that people will be more informed as to what we’re actually spending on classroom instruction as opposed to the social services and mental health and programs that are unrelated,” Richey said.

Another rising cost is related to districts hiring more administrative staff, even though student and teacher populations are both declining.

“We are seeing a disconnect in terms of the way that districts are staffing, especially in those positions that are substantially more costly when it comes to salaries and benefits,” Richey explained. “Central office staff is increasing exponentially in a direction that seems to be disconnected to the way that enrollment or the number of teachers is moving.”

As education departments spend more and more money managing and less money actually educating, lawmakers and policy experts are calling for greater accountability, as well as flexibility and parental control over education spending.

“[I do hope] that we can get to a point where we, like other states, can begin to recognize the value of the money following the student in a way that also protects the role of parents,” said Richey.

Pendergrass agrees.

“Programs that allow parents to choose a school for each of their children and that allow districts to specialize in what they offer should be welcomed,” she said. “It’s time to start thinking about how we can design a smarter system to better serve our region.”