Op-ed: Valid criticisms on gifted preschool programs fail to recognize homeschooling as ultimate ‘individualized instruction’

A recent Hechinger Report commentary skillfully highlighted the challenges of implementing gifted education programs for preschoolers, but it fell short of identifying a proven solution:…

A recent Hechinger Report commentary skillfully highlighted the challenges of implementing gifted education programs for preschoolers, but it fell short of identifying a proven solution: homeschooling.

“In an ideal world, experts say, there would be universal screening for giftedness (with) frequent entry — and exit — points for the programs,” Sarah Carr writes. “In the early elementary years, that would look less like separate gifted programming and a lot more like meeting every kid where they are.”

However, such “individualized instruction has frequently proved elusive with underresourced schools, large class sizes and teachers who are tasked with catching up the students who are furthest behind,” Carr laments.

As a homeschool graduate, I’ve experienced firsthand the benefits of “individualized instruction.” However, this never took place in traditional classrooms where educators must deal more with crowd management than customized academics.

It happened organically over time with my mom – a retired doctor with no previous teaching experience whatsoever – as my primary educator, mentor and guide.

Additionally, such “individualized instruction” is far more achievable than most people realize – simply because U.S. education historically took place outside government programs, “gifted” or otherwise, and inside the home.

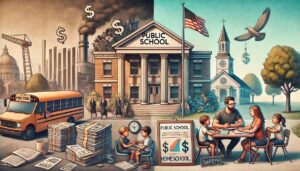

Public schools are the ‘experiment,’ homeschooling the historical norm

Most Americans during the colonial period learned “instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic and faith, morals, and interpersonal relationships or social skills” at home from their parents, historians note.

“The colonists were heir to Renaissance traditions stressing the centrality of the household as the primary agency of human association and education,” wrote Lawrence Cremlin, author of “American education: The colonial experience, 1607-1783.”

However, after more than 200 years of this model, the 1830s became a time of upheaval as Horace Mann worked to import the “Common School” movement – inspired by bureaucracies in Prussia and France – to the United States.

“Mann envisioned and campaigned for a more uniform, centralized, and government-controlled education system than had previously existed in America,” Daniel Lattier explained in an Intellectual Takeout article.

“Mann’s vision for American education eventually won out, but it was not without initial opposition. In 1840, a special legislative committee in Massachusetts had serious reservations about increasing government control over education. Interestingly, some of the reservations found in their final report … are very similar to those you hear echoed in concerns about America’s education system today.”

The late award-winning teacher John Taylor Gatto described parental resistance to this system in sobering terms:

“Our form of compulsory schooling is an invention of the state of Massachusetts around 1850. It was resisted – sometimes with guns – by an estimated 80% of the Massachusetts population, the last outpost in Barnstable on Cape Cod not surrendering its children until the 1880s when the area was seized by militia and children marched to school under guard.”

How this has led to our current ‘giftedness’ dilemma

All this may not seem immediately related to gifted education programs, which have drawn valid criticisms over their capacity to create (or exacerbate) inequities and abuses.

However, as Gatto notes, the problem lies within government education’s inherent design.

“The truth is that schools don’t really teach anything except how to obey orders,” he said.

“Schools were designed by Horace Mann and Barnard Sears and Harper of the University of Chicago and Thorndyke of Columbia Teachers College and some other men to be instruments of the scientific management of a mass population. Schools are intended to produce through the application of formulae, formulaic human beings whose behavior can be predicted and controlled.”

As a result, this “formulaic” approach extends to its search for giftedness – which assumes “it’s possible to assess a child’s potential, sometimes before they even start school,” Carr writes.

“After more than five decades, the city’s experience offers a case study in how elusive — and, at times, distracting — that quest remains.”

Carr outlines three main strategies for determining giftedness, all of them problematic:

- Cognitive testing, “which attempts to rate a child’s intelligence in relation to their peer group”

- Achievement testing, “which is supposed to measure how much and how fast a child is learning in school”

- Teacher evaluations, which “research has found … are less stable and predictive than the (already unstable) cognitive testing”

The first strategy, cognitive testing, comes under fire for loopholes such as paying private testers to evaluate children for giftedness and pushing children as young as 3 to take “pricey and extensive test prep,” according to Carr.

“‘I don’t know if everybody is paying,’ one parent told me at the time, ‘but it defeats the purpose of a public school if you have to pay $300 to get them in.’”

Achievement testing options, including “nonverbal tests,” don’t fare better on the equity scale.

“Children who’ve had more exposure to tests, problem-solving and patterns are still going to have an advantage,” and “scores can change significantly from year to year, or even week to week” for young ages such as 4, Carr notes.

Finally, teacher evaluations by their nature face inherent inconsistencies when dealing on a scale of hundreds of individuals.

“People are very bad at looking at another person and inferring a lot about what’s going on under the hood,” said Moritz Breit, post-doctoral researcher in the psychology department at the University of Trier in Germany.

“When you say, ‘Cognitive abilities are not stable, let’s switch to something else,’ the problem is that there is nothing else to switch to when the goal is stability. Young children are changing a lot.”

A return to ‘meeting every kid where they are’

Meanwhile, no one seems to realize the ultimate problem involves public schools’ fixation on identifying “giftedness” in the first place.

Perhaps Kathy Koch, a frequent commenter at homeschool conferences, says it best in the abstract of her book, “How am I Smart?”:

“At one time or another, most kids will ask (or secretly wonder), ‘Am I smart?’ But a better question is, ‘In what way am I smart?’ … Koch’s down-to-earth and practical guide to the theory of multiple intelligences helps parents and teachers discern and develop their children’s unique wiring.”

To achieve this, our educational system will need to look a lot more like homeschooling and a lot less like typical classroom instruction:

- Customizing specific learning strategies to the sensory needs of all children, particularly neurodivergent ones

- Covering the same amount of “strategic learning behavior” in 2 hours compared to an entire school day

- Contributing to documented higher levels of mental health, full-time employment and civic service

For centuries, elite families have paid handsome prices for the customized one-on-one tutoring that homeschool parents naturally provide their “students” at no extra charge.

However, these parents – unlike private tutors – often make financial sacrifices for their commitment to their children’s education. These can include downsizing to one-income households, working other jobs in addition to homeschooling, and postponing or skipping other moneymaking opportunities in exchange for more time at home.

Is it worthwhile? Most would immediately say yes – myself included – and longtime study also supports this.

The results speak for themselves in terms of homeschool graduates’ higher academic outcomes as well as social, emotional and psychological development, according to data gathered over 30 years by the National Home Education Research Institute.

Ironically, the Hechinger Report previously noted the “alterable curriculum of the home,” or parental influence, is twice as predictive of a child’s academic success as socioeconomic status. So why not encourage more of it?

Let’s stop wringing our hands over the failures of a broken public-school system while ignoring the alternatives springing up outside it.

Instead of trying to fit children into preconceived ideas of what giftedness should look like, let’s focus on homeschooling’s success in “meeting every kid where they are” – just as Carr suggested – to develop their strengths while also addressing areas for growth.