Risky uterine transplants might allow biological men to give birth. Is it ethical?

Doctors are considering an experimental surgery to enable biological males to become pregnant and give birth, and few are considering the ethics beyond the risk to the patient’s health.

Uterine…

Doctors are considering an experimental surgery to enable biological males to become pregnant and give birth, and few are considering the ethics beyond the risk to the patient’s health.

Uterine transplants (UTx) among women are rare, but allow a woman suffering from uterine factor infertility to conceive and carry a child.

The first successful woman-to-woman UTx took place in Europe in 2014. At least 100 have been performed since, resulting in 16 live births.

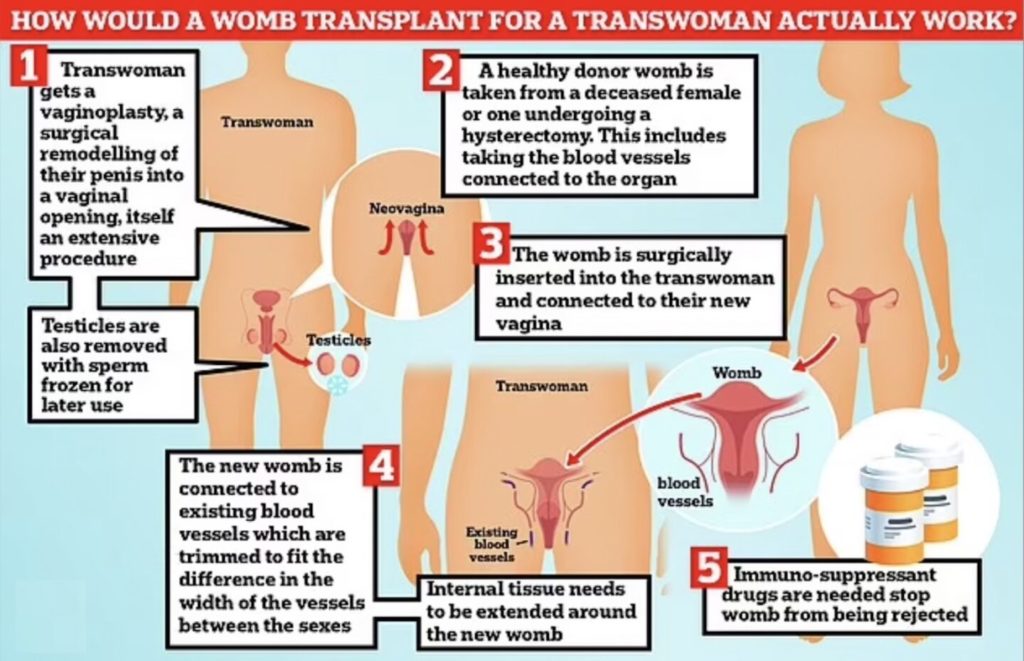

The process requires an initial transplant surgery, followed by immunosuppressant therapy, in vitro fertilization, and, if successful, a delivery of baby by C-section. A hysterectomy is the final step to remove the transplanted uterus.

According to Dr. Rebecca Flyckt, the process for a transgender woman – a biological male identifying as female – would require additional surgery, including the removal of male genitals. And a vaginoplasty.

Any UTx is risky, but even more so in a transgender woman, who has a greater risk of blood clots since male blood vessels are larger than female ones. And researchers admit that because the procedure is so new, other potential risks are unknown.

Nonetheless, Flyckt argues that offering UTx to transgender women is necessary to ensure equality.

“As we increasingly recognise a history of inequality and discrimination for transgender women, we must question whether it is acceptable that transgender women are denied access to clinical trials based on their gender identity and trans status,” she said.

According to Alicyn Simpson, donors could even be transgender men – biological women – who no longer want their female organs and can donate them to transgender women.

????Alicyn Simpson, who works at the UPMC Children’s Hospital Gender program, describes the possibilty of uterine transplants from LIVE DONORS being given to men who are trying to become women.

“Most transgender women would choose to have female physiological experiences.” pic.twitter.com/U09CCcQFNQ

— Megan Brock (@MegEBrock) January 12, 2023

Simpson, who works for the Gender and Sexual Development Program of University of Pittsburgh’s Children’s Hospital, claims surveys indicate many transgender women desire to have female physiological experiences, including pregnancy.

While the potential operations are just now receiving attention, the first transgender UTx was performed in 1931, though it was successful, leading to the suffering and death of the patient.

Lili Elbe, the protagonist portrayed in the Oscar-winning film The Danish Girl, was a biological male who underwent four highly experimental, sex reassignment surgeries, including UTx, in Europe. Elbe’s immune system rejected the transplanted uterus, leading to his death by cardiac arrest several months after the surgery.

Shortly before his passing, Elbe described the operation as “an abyss of suffering.”

Now, nearly 100 years later, medical professionals are ready to give the procedure another try.

Dr. Narendra Kaushik, a surgeon at a gender reassignment clinic in New Delhi, India, believes it’s the “future.”

“Every transgender woman wants to be as female as possible – and that includes being a mother,” Kaushik told The Mirror in 2022. “The way towards this is with a uterine transplant, the same as a kidney or any other transplant.

“This is the future. We cannot predict exactly when this will happen but it will happen very soon.”

Barbara Billauer, a professor of law and bioethics, emphasized how such a surgery would be extremely experimental.

“It’s not surprising then that the proposed uterine transplant to a trans-woman is to take place in India,” Billauer wrote. “In the US, experimental surgeries must be approved by a hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB). Given that most physicians consider the procedure too risky, approval would be highly unlikely.”

She also noted there isn’t sufficient research on the impact of immunosuppressant medicine on an unborn child.

Other medical ethicists have raised questions about the procedure – some of which also apply to other organ transplants – like whether such operations should be publicly funded, how to ensure donors are fully informed and give “high quality consent,” and how to conduct risk-benefit analysis.

One might also ask whether candidates for UTx surgery should be required to meet certain child-rearing standards, as the purpose of the operation is to produce a child.

However, it seems a bygone conclusion for some surgeons and researchers that if transgender uterine transplants are possible, they can and should be performed.

“There isn’t an ethical reason why [transgender women] should be denied access to the procedure,” said Dr. Jacques Balayla, an OBGYN in Canada.

“A woman who is born without a uterus and a man who transitions into a woman because of gender dysphoria have a similar claim to maternity if we consider them to have equivalent rights to fulfill the reproductive potential of their gender,” he claimed. “And I think that we should.”

However, J. Alan Branch, a professor of Christian ethics at Midwestern Seminary in Kansas City, believes such surgeries defy the purpose of medicine.

“The goal of medicine is either to maintain the human body in healthy status or to return the human body to healthy status after disease or injury,” Branch told The Lion. “Uterine transplants are not necessary for maintaining physical health nor do they return the body to pre-disease state of health.

“Elective gender reassignment surgeries, including uterine transplants, will modify perfectly functioning bodies and will intentionally damage them by introducing unnecessary, elective surgery with significant post-operative negative effects.”

Indeed, cross-sex treatments are known to come with gruesome side effects, including infections, hematomas, nerve injury, vaginal stenosis, and urinary tract damage.

“I want to emphasize that a man who has a uterine transplant will not be a woman,” concluded Branch. “He will be a man who has tragically altered his body.”

Nevertheless, a few surgeons in the world are poised to do what used to be only imagined by tabloid headlines.