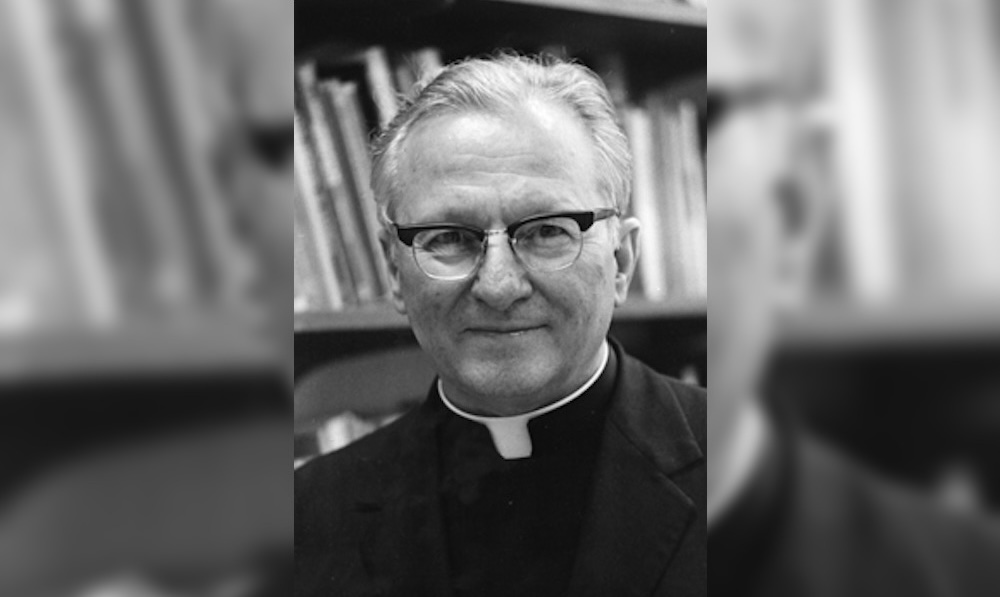

The ‘father’ of school choice you’ve never heard of: Father Virgil Blum

School choice proponents often credit Milton Friedman for starting this popular movement, but new scholarship suggests at least one other professor should get recognition where it’s due.

“We…

School choice proponents often credit Milton Friedman for starting this popular movement, but new scholarship suggests at least one other professor should get recognition where it’s due.

“We cannot fully understand the movement and the push for school choice policies of today without knowing something about another influential voice – Father Virgil Blum,” writes James Shuls in the Journal of School Choice.

Blum, one of Friedman’s contemporaries, taught political science at Marquette University from 1956 until 1978.

His Catholic faith as a Jesuit influenced his views on educational freedom, which he saw as part of the individual rights guaranteed in the First Amendment.

“In his lifetime, Blum produced hundreds of articles, speeches, and newspaper columns about educational topics, most having to do with public funding for children attending non-public schools,” writes William Fliss in his doctoral dissertation. “Over time, Blum came to resemble a pamphleteer of the American Revolutionary era, firing off his literary broadsides into the public square.”

First, Fourteenth Amendments

Blum’s doctoral dissertation, “Legal Aspects of Equality and Religious Liberty,” was published in 1954 – one year before Friedman published his now famous article, “The Role of Government in Education.”

The dissertation discusses how the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution helped secure personal faith-based freedoms by rejecting “an establishment of religion.”

This amendment was designed to help the fledgling nation avoid the situation in its mother country, where the Church of England required citizens to recognize only one form of religion, Blum argued.

“The denial to the Federal Government of the right to establish a (national) religion was intended as being purely instrumental to the securing of personal religious liberty,” he wrote.

However, federal courts have given the First Amendment a “false interpretation” of completely separating church from state – a phrase nonexistent in the amendment’s original language.

“The First Amendment, as now generally interpreted by the Federal Courts, has, in many cases, worked to the denial of that religious freedom guaranteed by the amendment. State courts, under the same limitation by reason of the Fourteenth Amendment, have, on many occasions, been guilty of the same violation of personal religious liberty.”

Therefore, children attending private Catholic schools were “deprived of equality under the law and the equal protection of the laws” simply for exercising their First Amendment rights, Blum concluded.

“Blum does not discuss vouchers, or certificates as it was sometimes known, but rather focused on the principle of funding for religious schools within specific examples,” Shuls writes. “In many ways, his arguments were precursors to the arguments that would ultimately win the day decades later.”

False concept of religious neutrality

Another of Blum’s main arguments debunked the assumption that public education could be religiously neutral.

“Every school in America has a religious orientation,” he wrote in 1960. “A school cannot be neutral with regard to God … If it excludes God as an important and integral part of things to be learned, its religious orientation is secularist.”

This reasoning continues today among school choice proponents such as former U.S. Attorney General William Barr.

“The threat today is not that religious people are about to establish a theocracy in the United States, it is that militant secularists are trying to establish an atheocracy,” Barr said in a 2022 speech.

“You can’t pretend what’s being taught in schools is compatible with traditional religion, nor can you pretend schools are neutral anymore.”

Blum also anticipated today’s school choice critics, who often demand parents pay themselves for faith-based alternatives to public schools.

“When government demands the surrender of freedom of choice in education as a condition for sharing in state educational benefits, it enforces conformity to the philosophical and theological orientation of government schools,” he wrote in 1958.

“There can be no free exchange of ideas, there can be no full and free discussion, when participation in the government’s educational benefits is conditioned on the surrender of educational freedom – the freedom to exchange ideas and to pursue truth uninhibited by the strong arm of the state.”

‘Foundational arguments’ for modern court rulings

Because freedom of religion was a civil right, the U.S. government violated individuals’ freedoms by withholding funds from people simply because of their religious affiliation, Blum argued.

“Freedom penalized is not freedom, but repression of freedom,” he wrote in 1966.

Blum lived in a time when federal courts were “increasingly hostile to religious liberty and the free exercise of religion,” Shuls noted.

However, this unassuming Midwestern professor helped set the legal and political arguments established in later court rulings recognizing school choice as constitutional.

“Blum’s legal arguments, as articulated in his doctoral dissertation and later writings, were at the vanguard for school choice litigation. Indeed, his writings offer many of the foundational arguments that would later be used to win the day for vouchers and funding for religious institutions.”

One major reason for Blum’s success in changing the political landscape involved his focus on parental rights.

“Blum believed that when a parent exercised their right to choose a school for their child, they should not lose out on educational benefits,” Shuls explained.

“To this end, Blum argued that freedom of choice in education was a civil right and neither the U.S. Constitution, nor the separation of church and state, prevented public funding from going to private schools. Rather, they required it.”

Shuls also documents Blum’s efforts to help parents in St. Louis found the Citizens for Educational Freedom (CEF) in 1959. This grassroots school choice organization expanded to more than 20,000 members in three years.

In fact, one of the parents credited for helping establish the organization coyly referred to Blum as the real originator.

“I think most people know the real Father of CEF; and he has no children, which surely does not fit my description,” wrote Vincent Corley, father of 10, to Blum in a personal letter dated Sept. 22, 1965.

While Blum’s contributions to the school choice movement were extensive, his name is scarcely recognized today. Scholars such as Shuls and Fliss are working to change this, noting his labor over more than 40 years to advance religious, legal and moral arguments for educational freedom.

“His legacy will endure along with other great American patriots in the annals of our history,” Shuls quotes from Blum’s obituary in 1990, “as a new day of freedom dawns for our people in the education of our children.”