What took so long? Schools return to phonics amid crisis in reading

American elementary schools could be trapped under the looming shadow of illiteracy, but the solution has been around for decades.

By 4th grade, students are expected to read for comprehension,…

American elementary schools could be trapped under the looming shadow of illiteracy, but the solution has been around for decades.

By 4th grade, students are expected to read for comprehension, and those who can’t read proficiently will be at a disadvantage for the rest of their education.

Reading below grade level is far too common in public schools. Testing data from 2022 showed that 66% of 4th graders in America can’t read at grade level.

But amidst this crisis of illiteracy, some states have found a proverbial knight in shining armor: tried-and-true phonics, or the “science of reading.”

The science of reading

Even in 2004, President George W. Bush advocated for the phonics-based approach saying, “Reading is more of a science than people think.”

But for decades, educators ignored the science and began using novel strategies.

As told in the podcast, Sold a Story, by award-winning journalist Emily Hanford, questionable approaches to teaching reading gained traction worldwide in the 1980’s and 1990’s.

The “whole language” approach taught students to read, not by sounding out letters but with techniques like using context to guess what the word might be or looking at just the first letter of the word.

These techniques were called the “three cueing” system.

Using modern technology – like MRIs – education researchers eventually found that whole language and cueing approaches weren’t effective. Instead, phonics – sounding out each letter to form a word – was the best method and was dubbed the “science of reading.”

Now, advocates for reading science are trying to retrain teachers in the older, proven ways.

Publishers cashed in on new methods

Some teachers were simply misled or didn’t believe the new science, but Hanford reveals in her podcast that the authors and publishers of reading textbooks may have had other motivations to continue pushing debunked reading techniques.

In 2019 alone, school districts nationwide spent over a billion dollars on reading programs for pre-K through 6th graders. Heinemann Publishing, whose curricula was on the forefront of the whole language approach, rakes in millions every year.

Hanford discovered that New York City’s Department of Education spent $21 million on Heinemann books over a decade. Georgia’s Gwinnett County Public Schools spent $14 million; Baltimore spent $11 million; Palm Beach in Florida, $9 million.

Overall, Heinemann made $226 million just from 84 of the nation’s largest school districts over a ten-year period. Those 84 districts account for one-sixth of the nation’s total K-12 public school population.

For phonics proponents, however, it’s better late than never for the science of reading, which is finally gaining traction again.

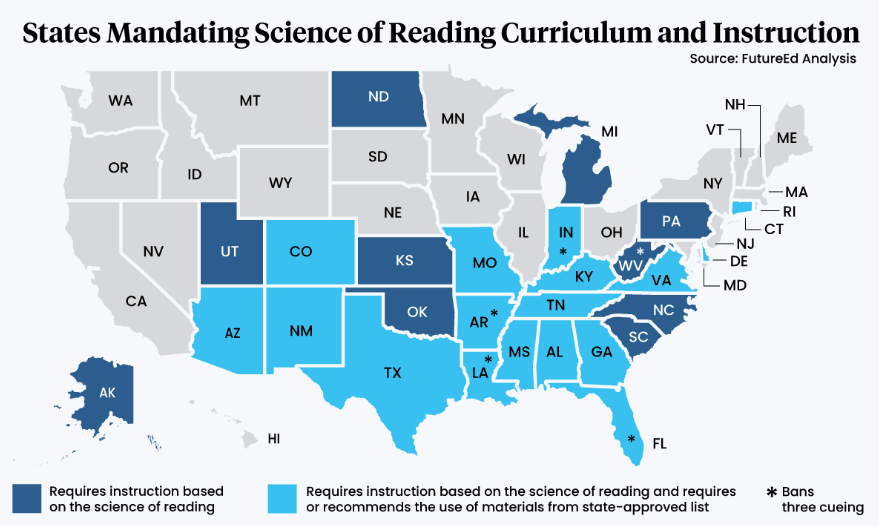

In recent years, dozens of states have passed laws intended to advance the science of reading. Education think tanks are promoting the methods, and 11 Mississippi elementary schools are even being designated “Emerging Science of Reading Schools” for successfully implementing the approach.

Mississippi has become a literacy leader after investing in reading science programs in 2013. A decade ago, its 4th grade reading scores were 49th in the nation. Now, it’s 21st.

“There is this ‘Mississippi miracle’ phrase,” said Kristen Wynn, Mississippi State Literacy Director. “It’s not for us a miracle that we took the time to stop and say there is a problem and we need to fix this problem.”

Other southern states have also enjoyed higher literacy rates after implementing the science of reading.