Birth of the abortion industrial complex (part 1): The “Race Betterment” Club

There’s a straight line from the heyday of Social Darwinism in the 19th century to the eugenics movement of the 1930s, through the…

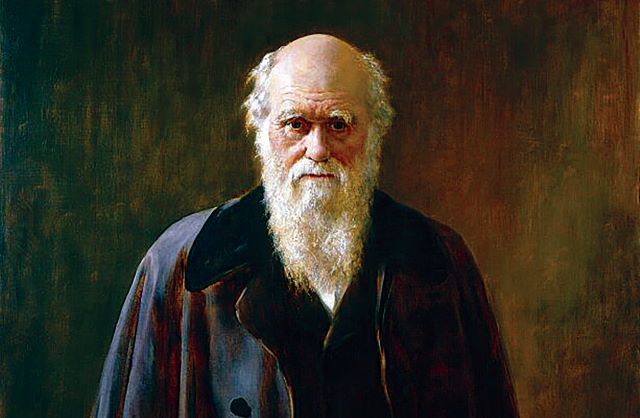

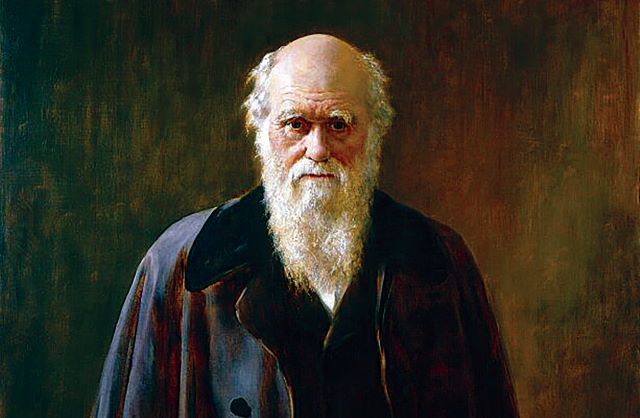

There’s a straight line from the heyday of Social Darwinism in the 19th century to the eugenics movement of the 1930s, through the death of the Third Reich. Credit: UK National Portrait Gallery. License: https://bit.ly/3OxPIo0.

(Capital Research) – There’s a straight line from the heyday of Social Darwinism in the 19th century to the eugenics movement of the 1930s, through the death of the Third Reich. It ends in population control, forced sterilization, the Sexual Revolution, and mass abortion. A century ago Western elites called it cutting-edge “science.” Today, they call it “philanthropy.”

Most Americans believe our society learned its lessons from trying to breed the perfect human, what German race thinkers called the “Übermensch.” Many also believe that subsequent attempts to stop population growth—especially by poor Indians, Asians, and Africans—are a mistake we’ve put behind us.

But these efforts at global social engineering never really died; they mutated. Today, we’re living with the poisonous fruit of more than a century of so-called progressives’ deadly pursuit of utopia. Call it the Abortion Industrial Complex: an industry that churns through billions of dollars each year trying to snuff out as much life as possible. This article exposes that industry’s dark origins by tracing the story of one pro-abortion network, which uses the profits from selling sex toys to terminate the lives of unborn Africans.

The “Race Betterment” Club

Eugenics (in Greek, “well-born,” “good stock,” or “beautiful offspring”) was a pseudoscience popular in the late 19th through mid-20th centuries derived from the theories of Darwinism and natural selection, but applied to humans. Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s cousin and close friend, coined the term. He saw eugenics as “the study of the agencies under social control that may improve or repair the racial qualities of the future generations, either physically or mentally.”

Like improving the quality of wheat, flowers, or horses through careful and intentional mating, Galton and his fellow eugenicists believed they could breed out undesirable traits in people: hereditary diseases, low intelligence, even ugliness.

Today, that idea sounds absurd and repulsive. But far from being a fringe movement, eugenics was wildly popular in its heyday—at least among elites—and lavishly funded. In 1906, Corn Flakes inventor John Harvey Kellogg (today’s left-wing W.K. Kellogg Foundation was founded by his brother) bankrolled the creation of the Race Betterment Foundation in Battle Creek, Michigan, to ensure that only individuals with the proper racial pedigree had children. In 1917, the Rockefeller family and Carnegie Institution of Washington (now the Carnegie Institute for Science) built the Eugenics Record Office at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island to support the heredity research of Charles Davenport, a brilliant biologist, statistician, and early geneticist, who founded the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations in 1925.

Eugenics also flourished alongside genuine scientific inquiry into heredity. Davenport laid important groundwork for James Watson and Francis Crick’s 1953 discovery of DNA’s double helix structure, research that was conducted at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Watson himself has defended the theory of eugenics while criticizing eugenic policies like forced sterilization and, in the Third Reich, murder. He’s also pointed out that eugenicists’ goal of creating a genetically perfect society is elusive:

The problem is that we’re not genetically equal . . . . So what do you do with the unfit? You can give them charity, you can try and cure their diseases . . . or Hitler’s solution was just kill them. But of course it wouldn’t have created the perfect race because a new unfit would have been created. And so it’s a constant problem that we have to deal with.

“I think the main lesson to be learned is the State shouldn’t make genetic decisions,” he’s said. Yet Watson’s point neatly illustrates why eugenics—whose advocates included some conservatives, such as Theodore Roosevelt and Winston Churchill—was championed by socialists, militant atheists, and the 20th-century Progressive movement: The theory jibed with their belief in the power of social engineering to retool entire nations. For these early and optimistic adopters, there was simply no limit to science’s ability to transform humanity and rid it of hunger, disease, poverty, war, and all other social evils. Curbing unwanted population growth through sterilization was an act of mercy.

The Supreme Court agreed in the 1927 case Buck v. Bell, with Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.—a Progressive and secularist hero—opining of Virginia’s forced sterilization law that just as “the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives” in public service the state is also free to curb reproduction “in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence.

It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. . . . Three generations of imbeciles are enough [emphasis].

These advocates coined the phrase “race betterment” to describe their work or, as Margaret Sanger and the early advocates for birth control termed it, “family planning”—a term used today by abortion activists largely ignorant of its origins. Sanger herself believed that the “Eugenic Movement and the Birth Control movement . . . should be and are the right and left hand of one body,” referring to the American Birth Control League, the immediate predecessor of Planned Parenthood. By “birth control” Sanger meant vastly more than contraception; it was an ideology of socialist liberation in which a nation used eugenic policies to engineer itself into utopia.

Adolf Hitler’s National Socialists took these ideas to their natural conclusion. Among the first statutes passed by Hitler’s government in 1933 was the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring, inspired by model legislation drafted by American Eugenics Society president Harry H. Laughlin. The statute established genetic health courts consisting of a judge and doctor with the power to forcibly sterilize individuals suffering from “deficiencies,” including alcoholism. By 1945, over 400,000 people were sterilized by these courts.

Far from disturbing British and American eugenicists, Germany’s law sparked campaigns for sterilization measures in their own countries. “Sterilization should not be considered a punishment,” the American Birth Control League declared in a press release signed by Sanger. It even suggested that pensions be paid to “all paupers, morons, feebleminded, mentally and morally deficient persons, who will submit to sterilization,” which they concluded was a much better solution than “pass[ing] them out a dole while they increase their numbers tenfold.”

In the next installment, Marie Stopes was the face of British family planning and eugenics.