School district quietly removes alarming ‘designer baby’ assignment with eugenic overtones after mother raises concerns

Students in a Missouri middle school were given a genetics assignment suggesting traits such as “skinny,” blond hair and gray or blue eyes are the most valuable.

If that sounds frighteningly…

Students in a Missouri middle school were given a genetics assignment suggesting traits such as “skinny,” blond hair and gray or blue eyes are the most valuable.

If that sounds frighteningly similar to eugenics, the monstrous and discredited view of racial improvement that motivated the likes of Hitler, you’re in good company: So thinks the mother who discovered the assignment and immediately contacted the district, Liberty Public Schools in Liberty, Missouri, a Kansas City suburb.

Jennifer Bishop might never have known about the Jan. 19 assignment if her eighth-grader hadn’t missed part of the class and been handed the materials to take home. She emailed the school that very night.

“I am the only eighth-grade parent that knows about it,” Bishop told The Lion on Monday, 11 days after her child brought it home.

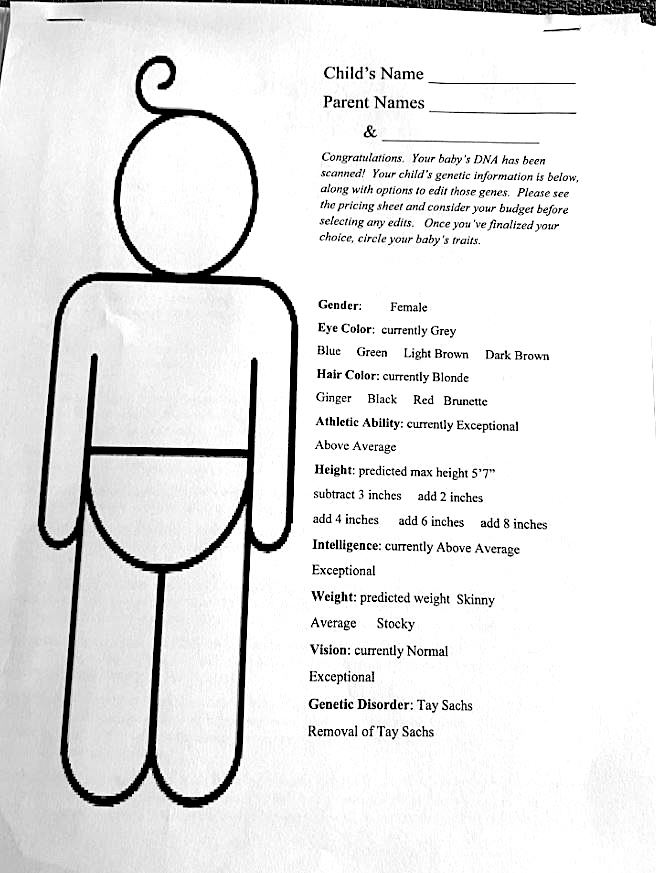

The assignment is called “designer baby” and is intended to teach students about the use of technology to alter genetics in organisms. The lesson was taught by middle school science teacher Staci Lester.

In the assignment, each student receives a worksheet representing a “baby” with a list of genetic traits such as gender, eye and hair color, intelligence and weight, as well as a genetic disorder. Under the baby’s given genetic traits are one or more alternatives that can be selected, but at a cost. Students are allowed varying but limited amounts of “money” to make alterations.

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Bishop

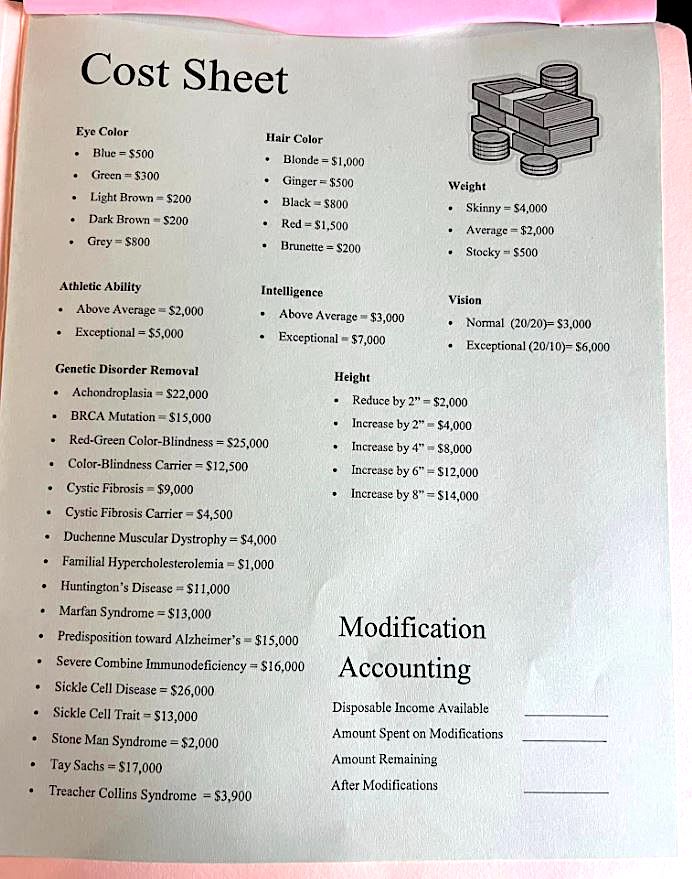

The accompanying cost sheet is particularly alarming, Bishop says, which led her to warn district officials in her initial email complaint about the possible connection to eugenics and even Hitler. The email was sent to numerous recipients, including Superintendent Jeremy Tucker, School Board President Nick Bartlow and Vice President Angie Reed, Chief Equity Officer Andrea Dixon-Seahorn and Principal Jill Mullen.

“I have no issue with teaching genetic disorders, but handing the students a child and asking them to ‘fix’ it indicates that the child has a ‘problem’ and that they can rectify the ‘problem’ with money and resources,” Bishop wrote in the email, which she shared with The Lion.

The cost sheet astonishingly values genetic characteristics such as blue eyes ($500) and blond hair ($1,000) more than brown eyes ($200) and black hair ($800) or brunette hair ($200). “Skinny” genes ($4,000) are worth eight times as much as “stocky” ones ($500). Increasing height becomes very expensive, as does improving athletic ability, intelligence and vision.

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Bishop.

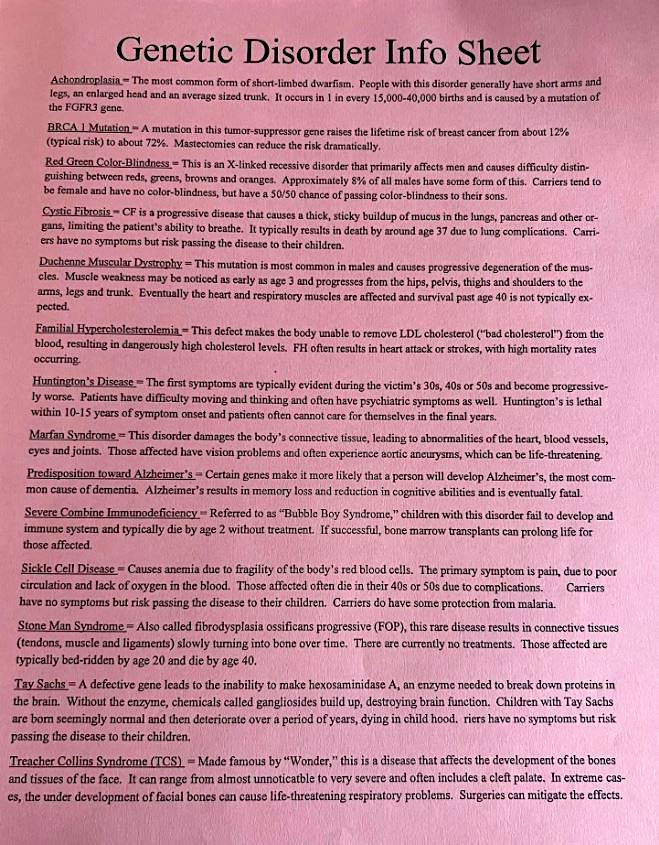

Then there is the frightening list of 17 genetic disorders, which are described in detail on a separate page. A disorder can be “removed,” most of them at great expense and sometimes beyond what a student can “afford,” which is designed to create an ethical dilemma and prompt classroom discussion.

Achondroplasia, “the most common form of short-limbed dwarfism,” for example, costs $22,000 to remove.

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Bishop.

In her email to district officials, Bishop described how some in her own family had experienced the health effects of genetic disorders, yet are “adored for the person that God created them to be.” She tells The Lion her own mother died from complications related to one of the disorders listed in the assignment, and her sister is disabled due to a genetic disorder.

Bishop’s child happened to be assigned a “baby” who suffered from the genetic disorder Tay Sachs. “Children with Tay Sachs are born seemingly normal and then deteriorate over a period of years, dying in childhood,” the worksheet explains. And in this case, it cost more to remove the disorder ($17,000) than the money allotted ($14,000).

“It kind of brought up the thought of instant resentment towards the baby,” Bishop says. “You know, ‘I can’t fix this child.’”

And while aborting the baby does not appear to be presented as an option, Bishop says one student decided to throw away his paper, which is arguably analogous to it.

“Genetic testing is currently not 100% accurate, and we know people that were told they shouldn’t be here because there would be something wrong with them,” Bishop wrote in her email to the school. “We are around many people who were also unwanted during pregnancy and survived failed abortions.”

‘No one is monitoring what is taught’

District officials seemed to immediately see the problems with the assignment, as revealed by replies to Bishop’s email sent the following day.

“We want you to know that as soon as we received your email – or in this case as it was forwarded to me by our Superintendent – we have been looking into this lesson,” Assistant Superintendent of Instructional Design Jeanette Westfall wrote to Bishop in an email sent Jan. 20 at 5:46 p.m. “We will not be using these materials at all moving forward.”

However, Bishop says the genetics lesson was continued earlier that day, although her child was excused from the class.

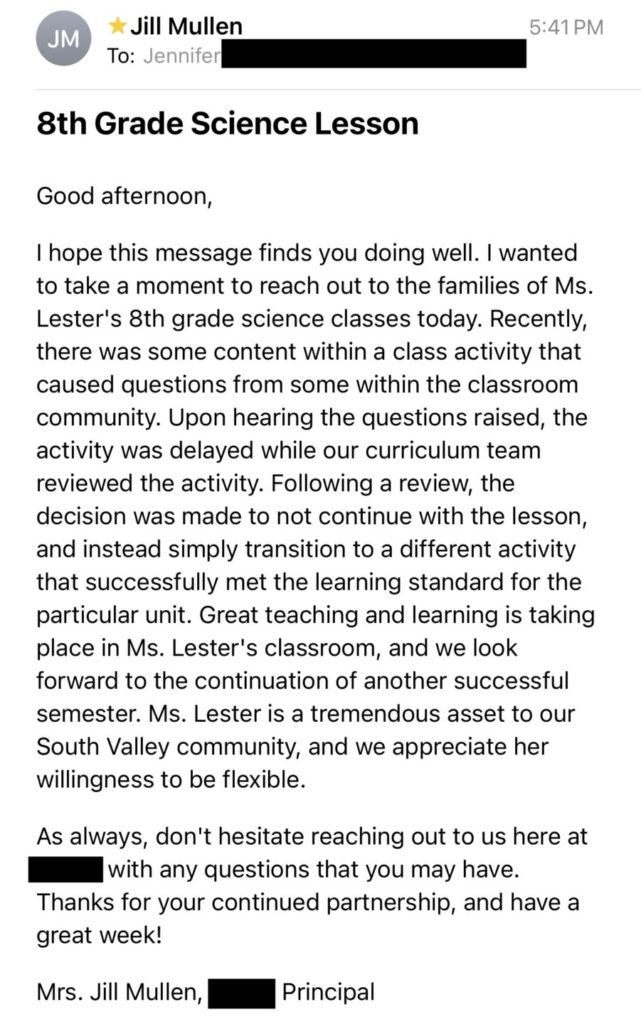

Principal Mullen sent a message to Bishop and all parents of Lester’s eighth-grade science students on Tuesday, 12 days after the assignment was given and only a few hours after The Lion contacted Mullen, Westfall, and Lester for comment on this story:

“Recently, there was some content within a class activity that caused questions from some within the classroom community. Upon hearing the questions raised, the activity was delayed while our curriculum team reviewed the activity.

“Following a review, the decision was made to not continue with the lesson, and instead simply transition to a different activity that successfully met the learning standard for the particular unit.”

Screenshot courtesy of Jennifer Bishop.

Notably absent is any description of the assignment, the topic or the reasons for discontinuing it.

Wednesday morning, Dallas Ackerman, the district’s director of communications, told The Lion the materials did not align with state standards:

“The district was made aware of the assignment and immediately contacted the teacher to check on the materials in question. The assignment was stopped by the teacher. The materials were not aligned with the state instructional standard and will not be used in our district.”

But parents will surely wonder how an assignment such as this, with its glaring inferences, was ever approved.

The truth is, it wasn’t approved, Bishop says.

In a meeting with school officials about the assignment on Jan. 26, which included two vice principals and Westfall – but not teacher Lester or principal Mullen – Bishop says she was told the district doesn’t review teacher lesson plans, and lessons plans are often created just two or three weeks in advance.

“The district has a new educational approach called ‘Competency-Based Learning,’ where teachers do not have their lesson plans reviewed, according to assistant superintendent Jeanette Westfall,” Bishop explained in an email.

Yet that educational approach is not mandated by the state and has little to do with reviews, says Rep. Doug Richey, R-District 38, who sponsored a bill in the Missouri House last year establishing a task force to explore it.

“Competency-Based Learning has nothing to do with whether lessons are reviewed or not,” Richey told The Lion. “It’s the idea that a teacher moves at the pace a student can handle.”

When asked about accountability, the district explained that teachers are reviewed periodically through “routine observations.”

“Lessons are created by teacher teams who are supported with professional learning around best practices. Teachers are accountable to aligning the activities with the instructional standard, and administrators review and evaluate staff through our Network for Educator Effectiveness (NEE) standards through routine observations,” Ackerman wrote.

That means the details of most lessons may never be reviewed by administrators. Instead, the district’s approach is to put out fires as they break out, Bishop says.

“[This] is the concern I have and I expressed to [Mrs. Westfall],” Bishop recalls about the meeting. “She’s going to continue to have problems in the school system. And she is putting out fires, but only once she’s been made aware of the fire.”

And while the district seems to agree with Bishop that the designer baby assignment needs extinguished, its creator isn’t so sure.

Heidi Hisrich, the science teacher who adapted the designer baby game from two high school seniors and made it available for other teachers to purchase online, says she always teaches it with “a background on eugenics and its horrors.”

“The teams of students are meant to be considering the potential for gene editing to be used in their lifetime and the associated ethical considerations,” Hisrich wrote in an email to The Lion. “Some students decide to make no edits at all, whereas others edit things like eye color and intelligence. This leads to a discussion of whether babies should be edited at all and, if so, what limits society should set. Also, different teams get different amounts of money, meant to prompt discussion and consideration of ‘fairness.’”

When asked whether the game and lesson should be altered to avoid the suggestion that children born with certain features or genetic aberrations are less valuable than others, Hisrich writes:

“I don’t know that the activity itself needs to be edited, so much as that it should be taught in context and with rich and careful discussion of these difficult topics. However, I’m open to hearing ideas of how the activity could be edited.”

Transparency: Parents don’t have the details

For Bishop, the discovery of the offensive genetics assignment was a fluke, owing to the coincidence of her child missing class and bringing it home. But how can parents discover what their children are learning at school?

“It’s hard,” Bishop says, even for her and her husband who are very intentional and engaged with their child’s learning.

Because the middle school issues iPads to its students, kids aren’t bringing papers home, she explains. And the details of assignments aren’t completely viewable through Canvas, the school’s online learning management software.

“The kids are 100% on iPads or MacBooks now, so we don’t get papers. We don’t. They’re not being taught from a textbook,” Bishop said. “So there really is no way for the parents to follow up on what is being taught, unless you’re talking to your kids.

“And if I’m being honest, I don’t know that [my child] could have described this to me, where I would have understood exactly what it was. So, it’s really hard to say.”

Bishop feels this incident is part of a larger disconnect between schools and parents.

“I feel like the school has pushed us [parents] out,” she says. “They’re making decisions for our kids without us being aware of them.”