Supers in this Kansas district want more money, higher property tax, no accountability

(The Sentinel) – The 2024 legislative agenda that Leavenworth County superintendents are proposing for adoption by their school boards is loaded with demands for legislators to increase funding,…

(The Sentinel) – The 2024 legislative agenda that Leavenworth County superintendents are proposing for adoption by their school boards is loaded with demands for legislators to increase funding, allow school boards to impose higher property taxes, and allow superintendents to do as they see fit with no accountability for student performance.

Predictably, it is focused on sustaining bureaucracies that produce relatively low outcomes, which, in most cases, remain below 2015 and 2019 pre-pandemic levels.

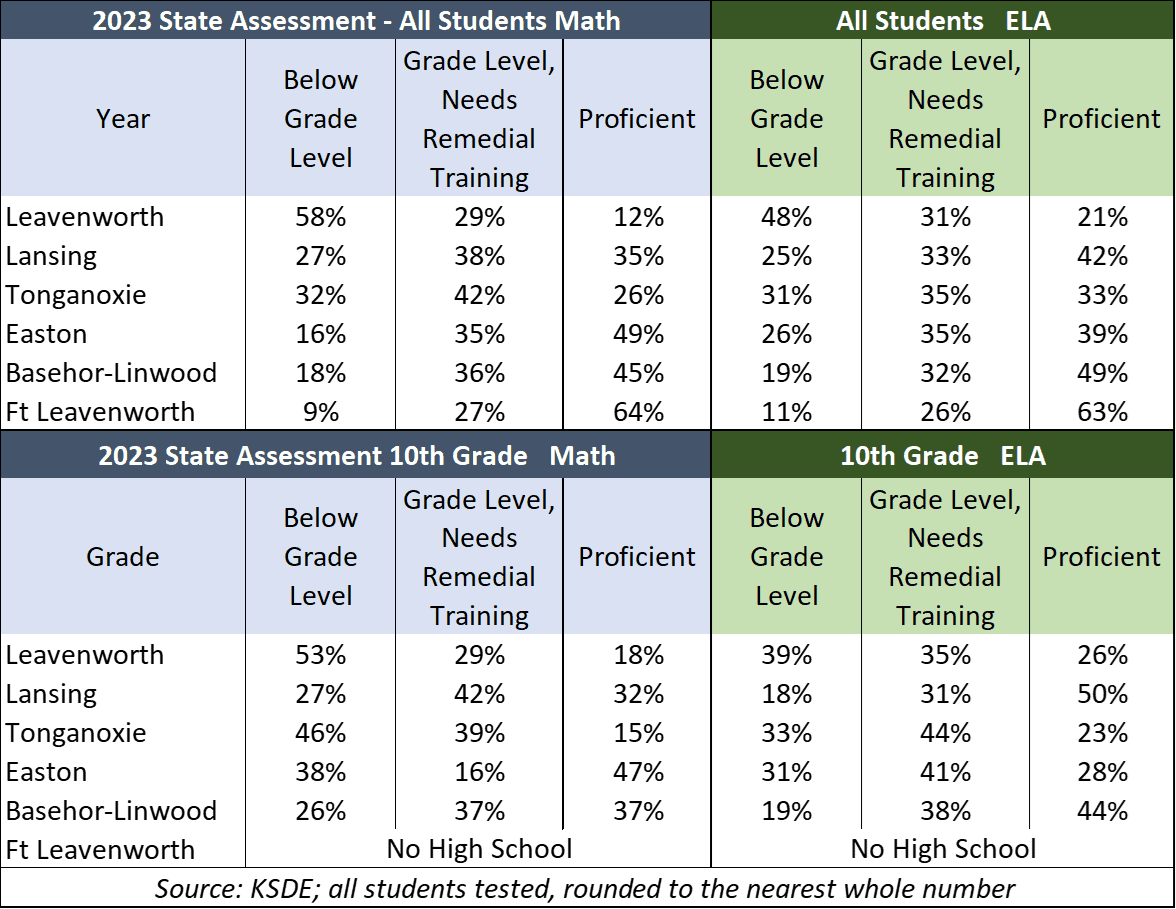

With the exception of USD 207 Fort Leavenworth, each district has less than half of its students proficient in Math and English Language Arts and a disturbing number of students below grade level.

There is little hope that outcomes will improve much under their 2024 legislative agenda because, for one thing, Leavenworth County districts, like most in Kansas, do not have strategic plans in place to achieve targeted improvements within specific time frames. Instead, they are loaded with objectives and action steps that are not measurable and therefore are devoid of accountability.

USD 453 Leavenworth, for example, has an objective “to meet individual student needs and support academic achievement in an engaging educational setting designed to produce postsecondary success.” That sounds nice, but district management can say they have met their objective with no improvement gains. Adult-focused objectives won’t help students become academically prepared for college and career. A student-focused objective for USD 453 might say, ‘Math proficiency will improve from 18% to 50%’ in a specified number of years.

State law requires school boards to conduct needs assessments annually in each school that identify barriers that prevent students from achieving proficiency, the budget changes needed to overcome those barriers, and the amount of time it will take for each student to become proficient. Yet, many school districts, including USD 453, ignore that legal obligation and avoid accountability, with statements to the effect of ‘many factors are out of our control, so giving a time estimate is not a realistic practice.’

Getting every student to be proficient isn’t realistic, and the Legislature should adjust that law. The Kansas Department of Education’s goal is 75% proficient, and student-focused board members should insist that districts at least identify the timeframe to achieve the KSDE goal.

Further, since many superintendents, at least including Lansing and Leavenworth, would not allow school board members to fulfill their legal obligation to conduct needs assessments in past years, the Legislature should impose consequences on districts that ignore the law.

Leavenworth supers: more money, higher property taxes, and less accountability

Leavenworth County superintendents want the Legislature to back off on accountability.

They don’t like laws that hold districts accountable for improving outcomes and requiring them to spend at-risk funding on extra services for academically at-risk students. They want that left to the jurisdiction of the State Board of Education, knowing that it and the Department of Education allow districts to violate laws with impunity.

To be accredited by the State, school districts must comply with state and federal laws, and even though two state audits determined that school districts are not spending at-risk funding as required, the State Board turns a blind eye.

With school funding exceeding $17,000 per student and over $1 billion in district bank accounts from state and local funding not spent in prior years, their money demands include:

- New money for “unfunded mandates.” (Incidentally, the Leavenworth superintendents say that providing services for dyslexia is an unfunded mandate rather than part of their job to teach kids to read.)

- New money for mental health services. Mental health is certainly an issue, but those needs might be better met by the professionals in state and local agencies. Superintendents could also ease mental health issues by stopping suggestions of gender dysphoria with young children and other controversial issues.

- Allow school boards to impose more property taxes. This one is camouflaged (“support greater opportunities for communities to utilize operational and capital funds at the local level”) but the intent is crystal clear. Districts want more authority to impose Local Option Budget and Capital Outlay taxes.

- Higher property valuation methods, described as “Property tax appraisal procedures that ensure adequate property tax revenue collection at the state and local level.” Superintendents must think that the 398% increase in the education property tax in Leavenworth County since 1997 is inadequate.

- More funding for early childhood, academically at-risk programs, transportation, teacher incentives, and “funding minimums for licensed teachers.”

Effective teachers should be paid more, but the Legislature is not to blame. That falls squarely on the shoulders of superintendents and school boards.

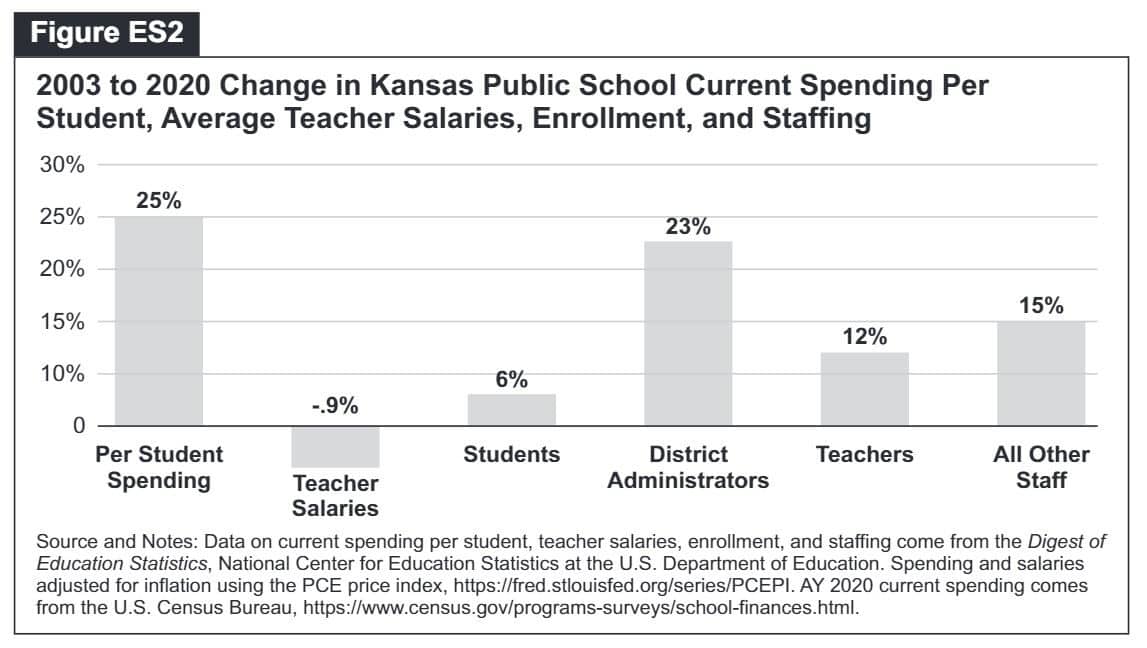

Dr. Benjamin Scafidi compared the inflation-adjusted change in per-student spending and teacher pay between 2003 and 2020 in a report published by Kansas Policy Institute (which owns the Sentinel). There was a 25% spending increase, but school districts reduced teacher pay by 0.9%.

Most of the increased funding was used to hire more people. With a 6% increase in students, school districts increased the number of teachers by 12%, hired 23% more administrators, and 15% more people in other positions. They also increased operating cash reserves by about $700 million between 2005 and 2020.

Student achievement can’t improve until adult behaviors change

The Leavenworth County superintendents’ legislative proposal is just the latest example of why student achievement cannot improve until adult behaviors change.

Adjusted for the cost of living, per-student spending in Kansas was the 9th highest in the nation in 2021, and that doesn’t include hundreds of millions that districts put in the bank over the years. School officials have plenty of money; they just need to spend it better.

Unfortunately, their spending history and tendency to flout state laws designed to improve achievement demonstrate that the Legislature needs to impose corrective consequences. Otherwise, legislators will effectively be accepting that about a third of Kansas kids will remain below grade level, and only about one in three will be proficient in reading and math.