The geography of school choice part II: the urban effect

Why hasn’t school choice made it out West?

Liv Finne, director of the Center for Education at Washington Policy Center, has an intriguing answer.

“I think it has primarily to…

Why hasn’t school choice made it out West?

Liv Finne, director of the Center for Education at Washington Policy Center, has an intriguing answer.

“I think it has primarily to do with the population density and the industrialization and urbanization of the east coast as compared to the West Coast,” Finne told The Lion.

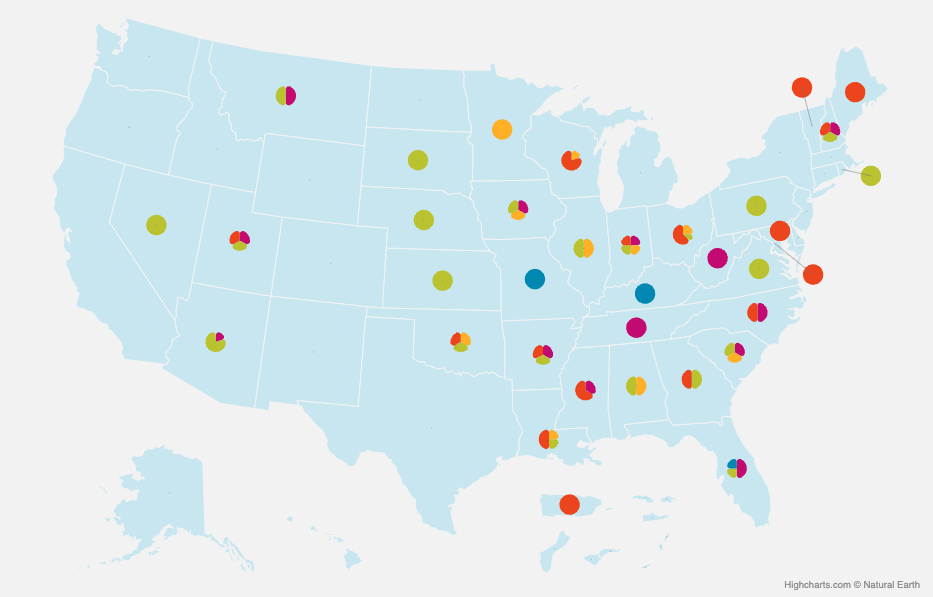

Here’s a map from 2018 representing each town in North America as a dot:

Now compare it to EdChoice’s school choice map.

What’s perhaps surprising is that the distribution has less to do with the dominant political perspective of states, red vs. blue.

As Finne explains, that’s because today’s partisan divide on education freedom wasn’t always the case.

“On the West Coast, many of the schools are in smaller, rural districts,” she said. “There’s a pushback in the rural districts of these small towns where half the people in the town are employed by the school district.”

In contrast, Finne says of typically more liberal paces, “In a big urban environment, you’ll have private school within the geographical distance of the homes.” And that proximity to public school alternatives makes school choice even more attractive to local residents suffering with poor educational outcomes.

In fact, Milwaukee – home of the first, modern-day voucher program – was a “democratic stronghold.”

“[The push for school choice was] led by minorities who were demanding access to alternatives to the underperforming public schools in their cities,” Finne explained.

‘It’s time that black people begin to look out for ourselves’

Rep. Annette Polly Williams was a firebrand Democrat who represented Milwaukee for 30 years in the State Assembly and sponsored the bill that created the Milwaukee Parental Choice voucher.

A Los Angeles Times article from 1990 frames the debate as a bitter racial struggle in which Williams was criticized for siding with white conservatives.

“The fact that the conservatives all support this, it doesn’t bother me one bit,” she said according to the Times. “I think it’s time that black people begin to look out for ourselves.”

Her opponents, who included public school superintendents and education officials, argued school choice would cripple public schools. Williams didn’t care.

“If the (public) schools can’t do any better than they’re doing now, then we don’t need them,” she responded.

And just like today, Williams relied on the support of parents to get her bill passed.

“We went to the parents first of the children who were suffering (in public schools), and we organized the parents,” Williams said. “The parents got the politicians in line … It’s a movement from the bottom up.”

According to Finne, a similar pattern played out in Washington, D.C., which launched a voucher program in 2004.

“The local minority leaders in the District of Columbia brought forward the Opportunity Scholarship program there demanding an option to the failing, underperforming schools in the District of Columbia,” she recalled, “and they got it.”

In the early 2000’s, D.C. test scores weren’t encouraging. Most high school sophomores (76%) tested “below basic” in math, and only 10% of 4th and 8th graders were at or above proficiency in reading.

But then D.C., which is 45% African American by population, elected a black, Democratic mayor, Anthony A. Williams, who helped get the voucher program passed.

“We had never had a locally elected black official, a Democrat from a city like D.C., asking for something like this before,” said Nina Shokraii Rees, a director at the U.S. Department of Education in 2006. “That’s the single strongest factor that got people’s attention.”

‘A limited perspective’

If dense, urban environments have poor public schools, it makes sense that parents and lawmakers will be more willing to demand change – especially if there are better options just up the street.

But that gumption isn’t as common in rural areas.

“The rural school districts in distant places across the heartland in Texas and in places like Wyoming, Montana, eastern Washington … a lot of representatives from that area don’t see the need for school choice,” explained Finne.

Some argue that school choice would harm rural communities because, unlike large cities, there aren’t many other options.

But Finne believes that’s “a limited perspective.”

“The research shows and it stands to reason that once you pass a school choice law allowing public dollars to go to a private school, you’re going to see a flourishing and a growth of new private schools,” she explained.